ja>Motoriyo |

|

| (同じ利用者による、間の5版が非表示) |

| 1行目: |

1行目: |

| − | {{Redirect|鳥}}

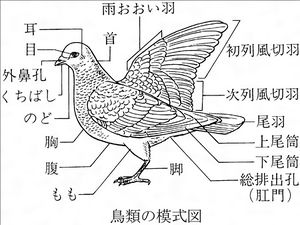

| + | [[ファイル:鳥類の模式図.jpg|サムネイル]] |

| | {{生物分類表 | | {{生物分類表 |

| | |名称 = 鳥綱 {{sname|Aves}} | | |名称 = 鳥綱 {{sname|Aves}} |

| | |fossil_range = 後期[[ジュラ紀]]–[[現世]]、{{Fossil range|150|0}} | | |fossil_range = 後期[[ジュラ紀]]–[[現世]]、{{Fossil range|150|0}} |

| | |色 = 動物界 | | |色 = 動物界 |

| − | |画像 = [[ファイル:Bird Diversity 2011.png|300px]] | + | |画像 = |

| − | |画像キャプション = 現存している鳥類およそ30の分類目のうち、<br />代表的な18種を示す。(クリックして拡大)

| |

| | |界 = [[動物|動物界]] {{sname||Animalia}} | | |界 = [[動物|動物界]] {{sname||Animalia}} |

| | |門 = [[脊索動物|脊索動物門]] {{sname||Chordata}} | | |門 = [[脊索動物|脊索動物門]] {{sname||Chordata}} |

| 11行目: |

10行目: |

| | |上綱 = [[四肢動物|四肢動物上綱]] {{sname||Tetrapoda}} | | |上綱 = [[四肢動物|四肢動物上綱]] {{sname||Tetrapoda}} |

| | |綱 = '''鳥綱''' {{sname||Aves}} | | |綱 = '''鳥綱''' {{sname||Aves}} |

| − | |学名 = [[w:Aves|Aves]]<br />{{AUY|Linnaeus|1758}}<ref>{{cite web |date=2014-01-26 |url= http://taxonomicon.taxonomy.nl/TaxonTree.aspx?id=80129&tree=0.1 |title=Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Taxon: Class Aves |work=Project: The Taxonomicon |publisher=Universal Taxonomic Services |accessdate=2014-06-21}}</ref> | + | |学名 = [[Aves]]<br />{{AUY|Linnaeus|1758}}<ref>{{cite web |date=2014-01-26 |url= http://taxonomicon.taxonomy.nl/TaxonTree.aspx?id=80129&tree=0.1 |title=Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Taxon: Class Aves |work=Project: The Taxonomicon |publisher=Universal Taxonomic Services |accessdate=2014-06-21}}</ref> |

| | |和名 = 「鳥(とり)」 | | |和名 = 「鳥(とり)」 |

| − | |英名 ="[[w:Bird|Bird]]" | + | |英名 ="[[Bird]]" |

| | |下位分類名 = 亜綱 | | |下位分類名 = 亜綱 |

| | |下位分類 = | | |下位分類 = |

| 19行目: |

18行目: |

| | }} | | }} |

| | | | |

| − | '''鳥類'''(ちょうるい)とは、'''鳥綱'''(ちょうこう、'''Aves''')すなわち[[脊椎動物亜門]]([[脊椎動物]])の一[[綱 (分類学)|綱]]<ref name="iwabio">岩波生物学辞典 第4版、928頁。</ref><ref name="kojien5">広辞苑 第五版、1751頁。</ref>に属する[[動物]]群の総称。日常語で'''鳥'''(とり)と呼ばれる動物である。 | + | '''鳥類'''(ちょうるい)'''鳥綱'''(ちょうこう、'''Aves''') |

| | | | |

| − | 現生鳥類 ([[w:Modern birds|Modern birds]]) は[[くちばし]]を持つ[[卵生]]の脊椎動物であり、一般的には(つまり以下の項目は当てはまらない種や齢が現生する)体表が[[羽毛]]で覆われた[[恒温動物]]で、[[歯]]はなく、[[前肢]]が[[翼]]になって、[[飛翔]]のための[[適応]]が顕著であり、[[二足歩行]]を行う<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_552-553>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、552-553頁</ref>。

| + | 脊椎動物門の鳥綱に分類される動物の総称。体は流線形で,[[羽毛]]に覆われる。 |

| | | | |

| − | == 概説 ==

| + | 口器は[[嘴]]になり,前肢は[[翼]]に変形しており,飛翔力は多くが備えているが,[[ダチョウ]]や[[ペンギン]]類など失った鳥もいる。 |

| − | {{仮リンク|現存分類群|en|Extant taxon|label=現存}}する鳥類は約1万種であり<ref name=IOC4.2>{{cite web |title=IOC World Bird List Version 4.2 |url=http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ |doi=10.14344/IOC.ML.4.2 |accessdate=2014-07-29}}</ref>(これまでの各分類に基づき、8,600種<ref name="iwabio" />や、9,000種<ref name="kojien5" />などとしているものもある)、[[四肢動物]]のなかでは最も種類の豊富な[[綱 (分類学)|綱]](分類目)となっている。現存している鳥類の大きさは[[マメハチドリ]]の5cmから[[ダチョウ]]の2.75mにおよび、体重はマメハチドリが2g<ref name=Yamagishi2002_36>[[#山岸2002|山岸 (2002)]]、36頁</ref>、ダチョウは100kgである<ref name=Gill_30>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、30頁</ref>。[[古生物学|化石記録]]によれば、鳥類は{{nowrap|1億5,000万}}年から{{nowrap|2億}}年前ごろの[[ジュラ紀]]の間に、[[獣脚類]][[恐竜]]から[[進化]]したことが示されている<ref name="AP-20140731">{{cite news |last=Borenstein |first=Seth |title=Study traces dinosaur evolution into early birds |url=http://apnews.excite.com/article/20140731/us-sci-shrinking-dinosaurs-a5c053f221.html |date=2014-07-31 |work=[[w:AP News|AP News]] |accessdate=2015-03-08}}</ref><ref name="SCI-20140731">{{cite journal |title=Sustained miniaturization and anatomical innovation in the dinosaurian ancestors of birds |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/content/345/6196/562 |date=1 August 2014 |journal=[[サイエンス|Science]] |volume=345 |issue=6196 |pages=562–566 |doi=10.1126/science.1252243 |accessdate=2 August 2014 |last1=Lee |first1=Michael S. Y. |first2=Andrea|last2=Cau |first3=Darren|last3=Naish|first4=Gareth J.|last4=Dyke}}</ref>。そして最も初期の鳥類として知られているのが、[[中生代]]ジュラ紀後期の[[始祖鳥]] (''Archaeopteryx'') で、およそ{{nowrap|1億5,000万}}年前である<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_1-2>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、1-2頁</ref>。現在では大部分の[[古生物学]]者が、鳥類を約{{nowrap|6,550万}}年前の[[K-T境界|K-T境界絶滅イベント]]を生き延びた、恐竜の唯一の[[系統群]]であると見なしている。

| |

| | | | |

| − | 現生鳥類の特徴は、羽毛があり、歯のない[[くちばし]]を持つこと、硬い殻を持つ卵を産むこと、高い[[代謝]]率、二心房二心室の[[心臓]]、そして軽量ながら強靭な[[骨格]]を持つことである<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_552-553 />。翼は前肢が進化したもので、ほとんどの鳥がこの翼を用いて飛ぶことができるが、[[平胸類]](走鳥類)や、[[ペンギン|ペンギン類]]、いくつかの島嶼に適応した[[固有種]]などでは翼が退化して飛べなくなっている。それでも現存する鳥類のすべての種が翼を持つが<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_552-553 />、数百年前に[[絶滅]]してしまった[[モア|モア類]]のように、完全に翼を失った例もある<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_805-806>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、805-806頁</ref>。また鳥類は飛翔することに高度に適応した、独特な[[消化器]]や[[呼吸器]]を持っている。ある種の鳥類、とりわけ[[カラス科|カラス類]]や[[オウム目|オウム類]]は最も知能の高い動物種のひとつであり、多くの種において{{仮リンク|動物の道具使用|en|Tool use by animals|label=道具を加工して使用}}することが観察されており、また、さまざまな社会的な種が、世代間の知識の文化的伝達<!--事例を示すべき-->を示している。

| + | [[定温動物]]で[[卵生]]のほか,骨格,内臓などに,飛行に有利な軽量化や[[代謝]]のための著しい[[適応]]が見られる。こうした特徴は約 6500万年前に絶滅したとされる[[恐竜]]も共有しているものがおり,鳥類は絶滅期を生き残った恐竜の系統であると考えられるようになった。 |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類は[[北極]]から[[南極]]に至る[[地球]]上の広範囲の[[生態系]]に生息している。また、多くの種が毎年長距離の[[渡り]]を行い、さらに多くが不規則な短距離の移動を行っている。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類は{{仮リンク|社会的行動|en|social behavior| label=社会的}}であり、視覚的な信号や、地鳴き (call)、さえずり ([[w:Bird vocalization|song]]) などの聴覚的な伝達行動を取り、そして{{仮リンク|巣のヘルパー|en|Helpers at the nest|label=協同繁殖}}や捕食(狩り)行動、群れ形成 ([[w:Flocking (behavior)|flocking]])、モビング([[w:Mobbing (animal behavior)|mobbing]]、偽攻撃、捕食者に対して群れをなして騒ぎ撃退する行動)などの社会的行動に加わる<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_330・798-799>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、330頁、798-799頁</ref>。大多数の種は社会的に[[一夫一婦制|一夫一婦]]であり、この関係は通常1回の繁殖期ごととなる。なかには数年にわたるのもあるが、生涯続くものは稀である。[[一夫多妻制|一夫多妻]](複数の雌)や、稀に[[一妻多夫制|一妻多夫]](複数の雄)の繁殖システムを持つ種も存在する。卵は通常、巣に産卵され、親鳥によって{{仮リンク|抱卵|en|Egg incubation}}される。ほとんどの鳥類は孵化後、しばらく続けて親鳥が雛(ひな)の世話をする。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 多くの種が経済的重要性を担っており、ほとんどは[[狩猟]]対象もしくは[[家禽]]であるが、なかには[[ペット]]として、とりわけ[[スズメ亜目|鳴禽類]]や[[オウム目|オウム類]]のように人気のある種もある。それ以外にも、[[グアノ]](鳥糞石)が[[肥料]]にするために採取される。鳥類は、[[宗教]]から[[ポピュラー音楽]]の歌詞にいたるまで、人間のあらゆる文化面によく登場する。しかし、分かっているだけで約130種の鳥が、17世紀以降の人間の活動によって絶滅し<ref name=Gill_626>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、626頁</ref><ref name=Yamashina2006_16>[[#山階2006|山階鳥研 (2006)]]、16頁</ref>、さらにそれ以前には数百種以上が絶滅している。保全への取り組みが進められてはいるが、現在約1,200種の鳥が、人的活動によって絶滅の危機に瀕している。

| |

| − | | |

| − | == 進化と分類学 ==

| |

| − | {{main|{{仮リンク|鳥類の進化|en|Evolution of birds}}}}

| |

| − | [[ファイル:Naturkundemuseum Berlin - Archaeopteryx - Eichstätt.jpg|alt= Slab of stone with fossil bones and feather impressions|thumb|right|[[始祖鳥]] (''Archaeopteryx'')。既知の最古の鳥類。]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | 最初の体系的な鳥類の[[分類]]は、1676年の書物、『鳥類学』 ''Ornithologiae'' において[[フランシス・ウィラビイ]]と[[ジョン・レイ (博物学者)|ジョン・レイ]]によって編み出された<ref name=Gill_77>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、77頁</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=del Hoyo |first=Josep |coauthors=Andy Elliott and Jordi Sargatal |title=[[w:Handbook of Birds of the World|Handbook of Birds of the World]], Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks |year=1992 |publisher=[[w:Lynx Edicions]] |location=Barcelona |isbn=84-87334-10-5}}</ref>。[[カール・フォン・リンネ]]は1758年に、この成果をもとに現在使用されている[[分類学|分類体系]]を考案した<ref>{{la icon}} {{Cite book |last=Linnaeus |first=Carolus |authorlink=w:Carolus Linnaeus |title=[[w:Systema Naturae|Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata]] |publisher=Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii) |year=1758 |page=824 |url=}}</ref>。鳥類は、{{仮リンク|リンネ式分類|en|Linnaean taxonomy}}では生物学的分類目の鳥[[綱 (分類学)|綱]] (class Aves) に分類される。{{仮リンク|系統命名学|en|Phylogenetic nomenclature|label=系統分類}}では鳥綱を恐竜である[[獣脚類]]の[[系統群]]に分類している<ref name="Theropoda">{{Cite journal |date=2007-01 |title=Higher-order phylogeny of modern birds (Theropoda, Aves: Neornithes) based on comparative anatomy. II. Analysis and discussion | journal=[[w:Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society|Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society]] |volume=149 |issue=1 | pages=1–95 |doi=10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00293.x |pmid=18784798 |last1=Livezey |first1=Bradley C. |last2=Zusi |first2=RL |pmc=2517308}}</ref>。鳥類とその姉妹群である[[ワニ]][[系統群]]には、 [[主竜類]]系統群の代表として現存する[[爬虫類]]が唯一含まれる。[[系統学|系統学的]]には通常、鳥類は現生鳥類と始祖鳥 (''Archaeopteryx'') の[[最も近い共通祖先]] (MRCA) の子孫のすべてであると定義されている<ref>{{Cite book|last=Padian |first=Kevin |authorlink=w:Kevin Padian |author2=L.M. Chiappe Chiappe LM |editor=[[w:Philip J. Currie|Philip J. Currie]] and Kevin Padian (eds.) |title=Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs |year=1997 |publisher=[[w:Academic Press|Academic Press]] |location=San Diego |pages=41–96 |chapter=Bird Origins |isbn=0-12-226810-5}}</ref>。始祖鳥(1億5,000万年ごろのジュラ紀後期<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_1-2/>)は、この定義のもとで最も古い既知の鳥である。一方、[[ジャック・ゴーティエ]]やファイロコード ([[w:PhyloCode|PhyloCode]]) システムの支持者たちは、鳥綱を現生鳥類だけを含む[[クラウン生物群]]として定義している。これは、化石のみで知られるほとんどのグループを鳥綱(鳥類)から除外し、代わって、鳥類およびそれらを '''[[鳥群]]''' (Avialae、「鳥の仲間」<ref name=Dave_208-209>[[#恐竜学入門|『恐竜学入門』 (2015)]]、208-209頁</ref>)に位置づけることがなされている<ref>{{Cite book|last=Gauthier |first=Jacques|editor=Kevin Padian |title=The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight|series= Memoirs of the California Academy of Science '''8'''|year=1986|pages=1–55|chapter=Saurischian Monophyly and the origin of birds|isbn=0-940228-14-9 |publisher=Published by California Academy of Sciences |location=San Francisco, CA}}</ref>。これはひとつには、伝統的に獣脚類恐竜と考えられている動物との関連における、始祖鳥の位置づけについての不確かさを回避するためである<!-- See WP:RS<ref>http://www.phylonames.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=7</ref> --><!--Mayr et al. 2005 "A well-preserved Archaeopteryx specimen with theropod features" + comment + Mayr's comment on the comment-->。

| |

| − | | |

| − | すべての現生鳥類は'''新鳥亜綱'''に位置づけられており、ここには2つの下位分類が存在する。[[古顎類]] (Palaeognathae) は飛べない[[平胸類]](走鳥類、たとえばダチョウなど)とほとんど飛べない[[シギダチョウ科|シギダチョウ類]]からなり、広く多様化している[[新顎類]] (Neognathae) はこれ以外のすべての鳥類を含む。この2つの下位分類はよく上目として扱われるが<ref>{{cite web|url=http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/birdbiogeography1.htm |last=Ritchison |first=Gary |title=Bird biogeography |accessdate=2014-06-22}}</ref> 、[[w:Bradley C. Livezey|Livezey]] や Zusi はこれを「[[コーホート]]」 ("Cohort") に位置づけている<ref name="Theropoda"/>。分類学的な観点により一様ではないが、現存している既知の鳥類の種数はおよそ9,700種以上<ref name=Gill_30 />、9,930種<ref>{{cite book |last=Clements |first=James F. |authorlink=w:James Clements |title=[[w:The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World|The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World]] |edition=6th |year=2007 |publisher=[[w:Cornell University Press|Cornell University Press]] |location=Ithaca, NY |isbn=978-0-8014-4501-9}}</ref>から10,530種<ref name=IOC4.2/>となる。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 恐竜と鳥類の起源 ===

| |

| − | {{main|{{仮リンク|鳥類の起源|en|Origin of birds}}}}

| |

| − | [[ファイル:Confuciusornis_sanctus_(2).jpg|thumb|alt= 無数のひび割れと、対になった長い尾羽を含む、鳥の羽と骨の痕跡のある白い岩の板。|中国で発見された白亜紀の鳥、[[孔子鳥]] (''Confuciusornis'')。]]

| |

| − | 大部分の科学者が、化石と生物学的な証拠から、鳥類が特殊化された獣脚類恐竜の亜群であることを認めている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Prum |first=Richard O. |title=Who's Your Daddy |journal=Science |volume=322 |pages=1799–1800 |year=2008 |month=December |doi=10.1126/science.1168808|pmid=19095929|issue=5909|issn=0036-8075}}</ref>。さらに具体的には、鳥類はそのなかでも[[マニラプトル類]]という、[[ドロマエオサウルス科|ドロマエオサウルス類]]や[[オヴィラプトル|オヴィラプトル類]]を含む[[獣脚類]]の仲間であるとする<ref name=Yamagishi2002_4-7>[[#山岸2002|山岸 (2002)]]、4-7頁</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Paul |first=Gregory S. |authorlink=w:Gregory S. Paul |chapter=Looking for the True Bird Ancestor |year=2002 |title=Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds |location=Baltimore |publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press |isbn=0-8018-6763-0 |pages=171–224}}</ref>。しかし、鳥類に関係の近い非鳥類型獣脚類の化石が発見されるたびに、それまで明瞭だった鳥類と非鳥類の区別が曖昧になっている<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_185>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、185頁</ref>。1990年代以降の中国東北部の[[遼寧省]]での発見では、多くの小形[[羽毛恐竜|獣脚類恐竜に羽毛があった]]ことが明らかになったが<ref name=Dave_217-220>[[#恐竜学入門|『恐竜学入門』 (2015)]]、217-220頁</ref>、それはこの曖昧さをさらに助長した<ref>{{Cite book |last=Norell |first=Mark |coauthors=Mick Ellison |year=2005 |title=Unearthing the Dragon: The Great Feathered Dinosaur Discovery |location=New York |publisher=Pi Press |isbn=0-13-186266-9 |pages=}}</ref>。それでも2014年には、研究者らにより獣脚類恐竜からの鳥類の進化の詳細が報告された<ref name="AP-20140731"/><ref name="SCI-20140731"/>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 現代[[古生物学]]における一致した見解は、鳥類ないし[[鳥群]] ([[w:Avialae|Avialae]]) は、ドロマエオサウルス類、[[トロオドン科|トロオドン類]]を含む、デイノニコサウルス類 ([[w:Deinonychosauria|Deinonychosauria]]) の最も近縁であるとする<ref name=Xiaotingia>{{cite journal |title=An ''Archaeopteryx''-like theropod from China and the origin of Avialae |url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v475/n7357/full/nature10288.html |date=28 July 2011 |journal=Nature |volume=475 |pages=465–470 |doi=10.1038/nature10288 |issue=7357 |author=Xing Xu, Hailu You, Kai Du and Fenglu Han |pmid=21796204}}</ref> 。さらに、これらは[[原鳥類]] ([[w:Paraves|Paraves]]) と呼ばれるグループを構成する。[[ドロマエオサウルス科]]の[[ミクロラプトル]](ミクロラプトル・グイ、''[[ミクロラプトル#M. gui|Microraptor gui]]'')<ref>{{Cite book|和書 |author=土谷健 |editor=小林快次監修 |year=2013 |title=そして恐竜は鳥になった |publisher=[[誠文堂新光社]] |isbn=978-4-416-11365-3 |pages=81-82}}</ref>など、このグループに属するいくつかの基系統群 ([[w:Basal (phylogenetics)|basal]]) は、滑空ないし飛行が可能であったかもしれない特徴を持っている。最も基系統であるデイノニコサウルス類は非常に小型であり、この証拠においては、原鳥類に属する祖先が、{{仮リンク|樹上性|en|Arboreal locomotion}}であったか、滑空することができたと考えられ、あるいはそのいずれでもあった可能性を提起している<ref name="AHTetal07">{{Cite journal |last=Turner |first=Alan H. |date=2007-09-07 |title=A Basal Dromaeosaurid and Size Evolution Preceding Avian Flight |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/reprint/317/5843/1378.pdf |format=PDF |journal=Science |volume=317 |pages=1378–1381 |doi=10.1126/science.1144066 |pmid=17823350 |month=September |issue=5843 |issn=0036-8075 |last2=Pol |first2=D |last3=Clarke |first3=JA |last4=Erickson |first4=GM |last5=Norell |first5=MA |accessdate=2014-06-22}}</ref><ref name="xuetal2003">{{Cite journal |last1=Xu |first1=Xing |last2=Zhou |first2=Zhonghe |last3=Wang |first3=Xiaolin |last4=Kuang |first4=Xuewen |last5=Zhang |first5=Fucheng |last6=Du |first6=Xiangke |year=2003 |month=January |title=Four-winged dinosaurs from China |journal=[[ネイチャー|Nature]]|volume=421 |issue=6921 |pages=335–340 |doi=10.1038/nature01342 |pmid=12540892 |issn=0028-0836}}</ref>。近年の研究では、初期の鳥類は、肉食であった始祖鳥や羽毛恐竜とは異なり、[[草食動物|草食]]であったことが示唆されている<ref>{{Cite web |date=2011-07-27 |url=http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/30969/title/On-the-Origin-of-Birds/ |title=On the Origin of Birds |publisher=[[w:The Scientist|TheScientist]] |accessdate=2014-06-21}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[ジュラ紀]]後期の始祖鳥は、最初に発見された[[ミッシングリンク]] (transitional fossils) のひとつとして有名であり、この化石は19世紀後期の[[進化論]]を支持する証拠となった<ref name=Dave_208>[[#恐竜学入門|『恐竜学入門』 (2015)]]、208頁</ref>。始祖鳥は、従来の爬虫類の特徴である、歯や、鉤爪のある指、そして長い[[トカゲ]]に似た[[尾]]のみならず、現生鳥類のそれと同様な[[風切羽]]を持つ翼の存在を、明瞭に示した最初の化石であった<ref name=Dave_207-209>[[#恐竜学入門|『恐竜学入門』 (2015)]]、207-209頁</ref>。始祖鳥は、現生鳥類の直接の祖先であるとは考えられていないが、おそらくは現生鳥類の真の祖先の近縁であった<ref name ="mayretal2007">{{Cite journal |doi=10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00245.x |last1=Mayr |first1=G. |last2=Phol |first2=B. |last3=Hartman |first3=S. |last4=Peters |first4=D.S. |year=2007 |title=The tenth skeletal specimen of ''Archaeopteryx'' |url= |journal=Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society |volume=149 |issue= |pages=97–116}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 異論と論争 ===

| |

| − | 鳥類の起源をめぐっては多くの論争が行われてきた。初期の意見の相違には、鳥類が恐竜あるいはより原始的な[[主竜類]]から進化したのかというものも存在する。恐竜陣営のなかにも、[[鳥盤類]]恐竜と[[獣脚類]]恐竜のいずれのほうが、より鳥類の祖先としてより近いかについて意見の相違があった<ref name="Heilmann1927">Heilmann, Gerhard (1927). ''The Origin of Birds''. New York: Dover Publications.</ref>。鳥盤類(鳥の骨盤を持つ)と現生鳥類は、骨盤の構造が共通であるが、鳥類は[[竜盤類]](トカゲの骨盤を持つ)恐竜が起源であると考えられている。したがってかれらの骨盤の構造は、互いに[[収斂進化|無関係に進化した]]ものである<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rasskin-Gutman |first=Diego |month=March |year=2001 |title=Theoretical morphology of the Archosaur (Reptilia: Diapsida) pelvic girdle |journal=[[w:Paleobiology (journal)|Paleobiology]] |volume=27 |issue=1 |pages=59–78|doi=10.1666/0094-8373(2001)027<0059:TMOTAR>2.0.CO;2 |last2=Buscalioni |first2=Angela D.|issn=0094-8373}}</ref>。事実、鳥類のような骨盤の構造は、{{仮リンク|テリジノサウルス科|en|Therizinosauridae}}として知られる獣脚類の特異なグループの進化において、3度出現している。

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[ノースカロライナ大学]]の鳥類古生物学者[[アラン・フェドゥーシア]]のような一部の少数派の研究者は、主流派の意見に異議を唱えており、鳥類が恐竜から進化したのではなく、[[ロンギスクアマ]]のような初期の爬虫類から進化したと主張している<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Feduccia |first=Alan |month=November |year=2005|title=Do feathered dinosaurs exist? Testing the hypothesis on neontological and paleontological evidence |journal=Journal of Morphology |volume=266 |issue=2 |pages=125–66 |doi=10.1002/jmor.10382 |pmid=16217748 |issn=0362-2525 |last2=Lingham-Soliar |first2=T |last3=Hinchliffe |first3=JR}}</ref>(この学説にはほとんどの[[古生物学|古生物学者]]が反対している<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Prum |first=Richard O. |month=April |year=2003 |title=Are Current Critiques Of The Theropod Origin Of Birds Science? Rebuttal To Feduccia 2002 |journal=[[w:The Auk|The Auk]] |volume=120 |issue=2 |pages=550–61 |doi=10.1642/0004-8038(2003)120[0550:ACCOTT]2.0.CO;2 |jstor=4090212|issn=0004-8038}}</ref>)。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 初期の鳥類の進化 ===

| |

| − | {{See also|化石鳥類の一覧}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | {{Cladogram

| |

| − | | cladogram = {{clade|style=font-size:80%

| |

| − | |label1=鳥綱

| |

| − | |1={{clade

| |

| − | |1=[[始祖鳥]]<br />''[[w:Archaeopteryx|Archaeopteryx]]''

| |

| − | |label2= [[w:Pygostylia|パイゴスティル類]]

| |

| − | |2={{clade

| |

| − | |1=[[孔子鳥]]<br />''[[w:Confuciusornis|Confuciusornis]]''

| |

| − | |label2= [[w:Ornithothoraces|鳥胸類]]

| |

| − | |2={{clade

| |

| − | |1=[[エナンティオルニス類]]<br />[[w:Enantiornithes|Enantiornithes]]

| |

| − | |label2= [[真鳥類]]

| |

| − | |2={{clade

| |

| − | |1=[[ヘスペロルニス類]]<br />[[w:Hesperornithiformes|Hesperornithiformes]]

| |

| − | |2=現生鳥類<br />[[w:Neornithes|Neornithes]]

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | | caption = 簡略化した基礎鳥類 (Basal bird) の系統発生<br />キアッペ (Chiappe)、2007 に基づく<!--Basal bird phylogeny simplified after Chiappe, 2007--><ref name="chiappe2007">{{cite book|last=Chiappe |first=Luis M. |year=2007 |title=Glorified Dinosaurs: The Origin and Early Evolution of Birds |location=Sydney |publisher=University of New South Wales Press |isbn=978-0-86840-413-4}}</ref>

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類の広範な形態への多様化は、[[白亜紀]]の間に起こった<ref name="chiappe2007"/>。鉤爪のついた翼や歯といったような、[[共有派生形質]]を維持したままのグループも多く存在したが、歯は、現生鳥類(新顎類)を含むいくつものグループで、個々に失われていった。始祖鳥や{{仮リンク|ジェホロルニス|en|Jeholornis}}のような最も初期の形態では、かれらの祖先が持っていた、長く骨のある尾を保持していたが<ref name="chiappe2007"/>、一方でパイゴスティル類に属するより進化した鳥類の尾は、{{仮リンク|尾端骨|en|Pygostyle}}の出現により短くなった。およそ9,500万年前の後期白亜紀には、すべての現生鳥類の祖先は、より優れた嗅覚を進化させた<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/news/4223/birds-survived-dino-extinction-with-keen-senses |title=Birds survived dino extinction with keen senses |author=Agency France-Presse|date=2011-04-13 |publisher=Cosmos Magazine |accessdate=2014-06-22}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 最初の、大規模で多様化した短尾の鳥類の系統として進化したのが、[[エナンティオルニス類]]、あるいは別名「反鳥類」である。このように命名されたのは、かれらの肩甲骨の構造が、現生鳥類のそれと反転していることに由来している。エナンティオルニス類は生態系において、[[渉禽類|渉禽]](しょうきん)のように砂浜で餌をあさるものや、魚を捕食するものから、樹上に棲むもの、種子を食べるものまで、多彩な[[ニッチ|生態的地位]](Ecological niche、生存環境の範囲<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_439-440>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、439-440頁</ref>)を占有した<ref name="chiappe2007"/>。さらに進んだ系統では、魚を捕食することに適応した、一見[[カモメ亜科|カモメ類]]に似た[[イクチオルニス]]属がある<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Clarke |first=Julia A. |coauthors= |month=September |year=2004 |title=Morphology, Phylogenetic Taxonomy, and Systematics of ''Ichthyornis'' and ''Apatornis'' (Avialae: Ornithurae) |journal=Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History |volume=286 |pages=1–179 |doi= 10.1206/0003-0090(2004)286<0001:MPTASO>2.0.CO;2|url=http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/bitstream/2246/454/1/B286.pdf|format=PDF|issn=0003-0090 |accessdate=2014-06-22}}</ref>。中生代の海鳥の目のひとつである{{仮リンク|ヘスペロルニス類|en|Hesperornithes|label=ヘスペロルニス目}}は、海洋環境における魚の捕食に非常によく適応して、飛翔する能力を失い、主として水中に生活するようになった<ref name="chiappe2007"/>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 現生鳥類の多様化 ===

| |

| − | {{See also|シブリー・アールキスト鳥類分類|{{仮リンク|恐竜の分類|en|dinosaur classification}}}}

| |

| − | すべての現生鳥類を含む系統である[[真鳥類|真鳥亜綱]]が、白亜紀の終わりまでにいくつかの現代の系統へと進化したことが、主に {{Snamei|en|Vegavis}} 属の発見によって現在わかっている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Clarke |first=Julia A. |month=January |year=2005 |title=Definitive fossil evidence for the extant avian radiation in the Cretaceous |journal=Nature |volume=433 |issue=7023 |pages=305–308 |doi=10.1038/nature03150 |pmid=15662422 |url=http://www.digimorph.org/specimens/Vegavis_iaai/nature03150.pdf|format=PDF |last2=Tambussi |first2=CP |last3=Noriega |first3=JI |last4=Erickson |first4=GM |last5=Ketcham |first5=RA |accessdate=2014-06-23}} [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v433/n7023/suppinfo/nature03150.html Nature.com] - 概要</ref>。そして2つの上目、すなわち[[古顎類]]と[[新顎類]]に分岐した。古顎類には平胸類(走鳥類)とシギダチョウ類が含まれる。もう一方の新顎類からの基系統 (basal) の分岐が、上目としての[[キジカモ類]](キジカモ上目、Galloanserae)のグループであり、これには[[カモ目]]([[カモ|カモ類]]、[[雁|ガン類]]、[[ハクチョウ|ハクチョウ類]]、[[サケビドリ科|サケビドリ類]])と[[キジ目]]([[キジ亜科 (Sibley)|キジ]]、[[ライチョウ亜科 (Sibley)|ライチョウ類]]およびその仲間に加えて、[[ツカツクリ科|ツカツクリ類]]、[[ホウカンチョウ科]]の鳥およびその仲間)が含まれる。この分岐の起こった年代は、科学者により盛んに議論されている。真鳥亜綱が白亜紀に進化し、ほかの新顎類からキジカモ類が分かれたのが、[[K-T境界|K-T境界絶滅イベント]]の前であることについては意見の一致が見られたが、これ以外の新顎類の[[適応放散]]が起きたのが、鳥類以外の恐竜の絶滅以前であるのか、あるいは絶滅以降であったのかについては意見が異なる<ref name="Ericson">{{citation|last=Ericson |first=Per G.P. |month=December |year=2006 |title=Diversification of Neoaves: Integration of molecular sequence data and fossils |journal=[[w:Biology Letters|Biology Letters]] |volume=2 |issue=4 |pages=543–547 |doi=10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523 |pmid=17148284 |url=http://www.mrent.org/PDF/Ericson_et_al_2006_Neoaves.pdf |format=PDF |issn=1744-9561 |last2=Anderson |first2=CL |last3=Britton |first3=T |last4=Elzanowski |first4=A |last5=Johansson |first5=US |last6=Källersjö |first6=M |last7=Ohlson |first7=JI |last8=Parsons |first8=TJ |last9=Zuccon |first9=D |pmc=1834003}}</ref> 。この意見の不一致の原因は、部分的な証拠の相違によるものである。すなわち、化石記録の証拠が[[第三紀]]に適応放散が起きたことを示すにもかかわらず、分子年代測定は白亜紀の適応放散を示唆している。これらの証拠を調整しようとする試みでは、意見の分かれるところとなった<ref name="Ericson"/><ref>{{citation|last=Brown |first=Joseph W. |month=June |year=2007 |title=Nuclear DNA does not reconcile 'rocks' and 'clocks' in Neoaves: a comment on Ericson ''et al.'' |journal=[[w:Biology Letters|Biology Letters]] |volume=3 |issue=3 |pages=257–259 |doi=10.1098/rsbl.2006.0611 |pmid=17389215 |issn=1744-9561 |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2464679/ |last2=Payne |first2=RB |last3=Mindell |first3=DP |pmc=2464679}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類の分類は議論の絶えない分野である。[[チャールズ・シブリー|シブリー]]と[[ジョン・アールクィスト|アールキスト]]の「[[シブリー・アールキスト鳥類分類]]」 ''Phylogeny and Classification of Birds'' (1990) は、鳥類の分類における画期的な業績であり<ref>{{Cite book|last=Sibley |first=Charles |authorlink=w:Charles Sibley |coauthors=[[ジョン・アールクィスト|Jon Edward Ahlquist]] |year=1990 |title=Phylogeny and classification of birds |location=New Haven |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=0-300-04085-7}}</ref>、それは頻繁に議論され、絶えず修正されている。ほとんどの証拠は、分類における目 (order) の位置づけが正確であることを示唆するように見えたが<ref>{{Cite book|last=Mayr |first=Ernst |authorlink=w:Ernst W. Mayr |coauthors=Short, Lester L.|title=Species Taxa of North American Birds: A Contribution to Comparative Systematics |series=Publications of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, no. 9 |year=1970 |publisher=Nuttall Ornithological Club|location=Cambridge, Mass. |oclc=517185}}</ref>、2000年代後半に判明した分子系統により、いくつかの目分類は大幅な修正を受けた。目そのものの相互関係についても、研究者の意見は一致していない。現生鳥類の解剖学、化石、DNA などあらゆる証拠が問題解決のために用いられてきたが、強いコンセンサスは得られていない。しかし近年には、新たな化石や分子解析による証拠から、現生鳥類の目の進化に関して、徐々に新しい知見がもたらされるようになってきている。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 現生鳥類の目分類 ===

| |

| − | {{See also|古顎類|新顎類}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | {{Cladogram

| |

| − | | cladogram =

| |

| − | {{clade|style=font-size:small; line-height:1em;

| |

| − | |label1=[[w:Neornithes|新鳥類]]

| |

| − | |{{clade

| |

| − | |[[古顎類]] {{sname||Paleognathae}}

| |

| − | |label2=[[新顎類]]

| |

| − | |{{clade

| |

| − | |[[キジカモ類]] {{sname||Galloanserae}}

| |

| − | |{{sname||Neoaves}}

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | | caption = 現生鳥類の基系統 (basal) の多様化

| |

| − | }}

| |

| − | | |

| − | 以下の目分類は、[[国際鳥類学会]] (IOC) による目分類である。シブリー分類のような全面的な変更はないが、伝統的な目分類に対する修正により、ほぼ系統分類となっている。これらの修正は、初期の分子系統分類 [[シブリー・アールキスト分類|シブリーら (1990)]] や、最新の形態系統分類 Livezey & Zusi (2007) などと共通点は少ない<ref name="Hackett"/>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 目レベルまでの系統は完全には解かれていないが、系統は、以下のような分類群が提案されている(ただし {{en|landbirds}} 〈陸鳥〉は正式な分類群ではない)。これらの系統は、有望な[[レトロポゾン]]によるものや<ref name="Suh">{{Cite journal | url=http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v2/n8/full/ncomms1448.html |first=Alexander |last=Suh |last2=''et al''. | title=Mesozoic retroposons reveal parrots as the closest living relatives of passerine birds |journal=Nature |volume=2 |year=2011 |number=8 | doi=10.1038/ncomms1448 |accessdate=2014-06-25}}</ref>、近年の複数の研究 (Hackett, 2008<ref name="Hackett">{{Cite journal |last=Hackett |first=S.J. |last2=''et al.'' |date=2008-07-12|title=A Phylogenomic Study of Birds Reveals Their Evolutionary History |url=http://www.owlpages.info/downloads/A_Phylogenomic_Study_of_Birds_Reveals_Their_Evolutionary_History.pdf |format=PDF |journal=Science |volume=320 |issue=5884 |pages=1763-1768 |accessdate=2014-06-25}}</ref>; Mayr 2011<ref name="Mayr">{{Cite journal |last=Matr |first=Gerald |title=Metaves, Mirandornithes, Strisores and other novelties – a critical review of the higher-level phylogeny of neornithine birds |url=http://www.senckenberg.de/files/content/forschung/abteilung/terrzool/ornithologie/metaves_review.pdf |format=PDF |journal=J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. | doi=10.1111/j.1439-0469.2010.00586.x | year=2011 | volume=49 | number=1 | page=58–76 |accessdate=2014-06-25}}</ref>) で支持されている。

| |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="font-size:small"

| |

| − | | colspan="5" | [[古顎類]] {{sname||Palaeognathae}}

| |

| − | | [[シギダチョウ目]] {{sname||Tinamiformes}}、[[ダチョウ目]] {{sname||Struthioniformes}}、[[レア目]] {{sname||Rheiformes}}、[[ヒクイドリ目]] {{sname||Casuariiformes}}、[[キーウィ目]] {{sname||Apterygiformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | rowspan="9" | [[新顎類]]<br />{{sname||Neognathae}}

| |

| − | | colspan="4" | [[キジカモ類]] {{sname||Galloanserae}}

| |

| − | | [[キジ目]] {{sname||Galliformes}}、[[カモ目]] {{sname||Anseriformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="4" style="border-bottom:none" | {{sname||Neoaves}}

| |

| − | | [[ネッタイチョウ目]] {{sname||Phaethontiformes}}、[[サケイ目]] {{sname||Pteroclidiformes}}、[[クイナモドキ目]] {{sname||Mesitornithidae}}、[[ハト目]] {{sname||Columbiformes}}、[[ジャノメドリ目]] {{sname||Eurypygiformes}}、[[ツメバケイ目]] {{sname||Opisthocomiformes}}、[[ノガン目]] {{sname||Otidiformes}}、[[カッコウ目]] {{sname||Cuculiformes}}、[[ツル目]] {{sname||Gruiformes}}、[[エボシドリ目]] {{sname||Musophagiformes}}、[[チドリ目]] {{sname||Charadriiformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | rowspan="7" style="border-top:none" |

| |

| − | | colspan="3" | {{sname||Mirandornithes}}<ref>{{cite | last=Sangster | first=G. | year=2005 | doi=10.1111/j.1474-919x.2005.00432.x | title=A name for the flamingo-grebe clade | journal=[[:en:Ibis (journal)|Ibis]] | volume=147 | page=612–615 }}</ref>

| |

| − | | [[カイツブリ目]] {{sname||Podicipediformes}}、[[フラミンゴ目]] {{sname||Phoenicopteriformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="3" | {{sname|Strisores}}<ref name="Mayr"/>

| |

| − | | [[ヨタカ目]] {{sname||Caprimulgiformes}}、[[アマツバメ目]] {{sname||Apodiformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="3" | {{sname||Aequornithes}}<ref name="Mayr"/>

| |

| − | | [[アビ目]] {{sname||Gaviiformes}}、[[ペンギン目]] {{sname||Sphenisciformes}}、[[ミズナギドリ目]] {{sname||Procellariiformes}}、[[コウノトリ目]] {{sname||Ciconiiformes}}、[[ペリカン目]] {{sname||Pelecaniformes}}、[[カツオドリ目]] {{sname||Suliformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="3" style="border-bottom:none" | {{en|landbirds}}<ref name="Ericson"/>

| |

| − | | [[ノガンモドキ目]] {{sname||Cariamiformes}}、[[タカ目]] {{sname||Accipitriformes}}、[[フクロウ目]] {{sname||Strigiformes}}、[[ネズミドリ目]] {{sname||Coliiformes}}、[[オオブッポウソウ目]] {{sname||Leptosomatiformes}}、[[キヌバネドリ目]] {{sname||Trogoniformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | rowspan="3" style="border-top:none" |

| |

| − | | colspan="2" | {{sname||Picocoraciae}}<ref name="Mayr"/>

| |

| − | | [[サイチョウ目]] {{sname||Bucerotiformes}}、[[キツツキ目]] {{sname||Piciformes}}、[[ブッポウソウ目]] {{sname||Coraciiformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="2" style="border-bottom:none" | {{sname|Eufalconimorphae}}<ref name="Suh"/>

| |

| − | | [[ハヤブサ目]] {{sname||Falconiformes}}

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | style="border-top:none" |

| |

| − | | {{sname||Psittacopasserae}}<ref name="Suh"/>

| |

| − | | [[オウム目]] {{sname||Psittaciformes}}、[[スズメ目]] {{sname||Passeriformes}}

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[ファイル:Neoaves Alternative Cladogram.png|thumb|400px|right|Neoaves の2つの姉妹群 Coronaves と Metaves<ref>[http://tolweb.org/Neoaves/26305 Tolweb.org], "Neoaves". ''Tree of Life Project''</ref>]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | 現生鳥類は[[古顎類]]と[[新顎類]]に分かれ、新顎類は[[キジカモ類]]と {{sname||Neoaves}} に分かれる。鳥類の現生種のうち、古顎類は0.5[[パーセント|%]]、キジカモ類は4.5%を占めるにすぎず、{{sname|Neoaves}} に種の95%が含まれる。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 古顎類は従来、[[胸骨]]に[[竜骨突起]]を残すシギダチョウ類と、竜骨突起を喪失した[[平胸類]](走鳥類〈[[ダチョウ目|ダチョウ類]]〉)に分けられてきたが、平胸類の単系統性が分子系統により否定された<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Harshman |first=John |last2=''et al''. |year=2008 |title=Phylogenomic evidence for multiple losses of flight in ratite birds |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci |volume=105 |url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2533212 |accessdate=2014-06-28 }}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | {{sname|Neoaves}} は鳥類のなかで最も適応放散した群だが、その下位分類は確定していない。シブリーらを含む以前の試みのほとんどは、実際の系統を反映していないことが判明し、現在の分類に残っていない。Ericson ''et al.'' (2006)<ref name = "Ericson"/>は {{sname|Neoaves}} が2つの姉妹群 {{sname||Coronaves}} と {{sname||Metaves}} に分かれるとし、Hackett ''et al.'' (2008)<ref name="Hackett"/>にも弱く支持されたが、異論もある<ref name="Mayr"/>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | == 分布 ==

| |

| − | {{See also|{{仮リンク|地域別鳥類一覧|en|Lists of birds by region}}}}

| |

| − | [[ファイル:House sparrow04.jpg|thumb|left|alt= 模様のある翼と頭に、明るい色の腹と胸をした小さな鳥がコンクリートの上にいる。 |[[イエスズメ]]の生息域は人間の活動によって、劇的に拡大した<ref>{{Cite book|last=Newton |first=Ian|year=2003 |title=The Speciation and Biogeography of Birds |location=Amsterdam |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=0-12-517375-X|page=463}}</ref>。]]

| |

| − | 鳥類の生活と繁殖は、ほとんどの陸上生息地で営まれており、これらは7大陸すべてで見ることができる。その南限は[[ユキドリ]]の繁殖地で、[[南極大陸]]の内陸 {{convert|440|km|mi|-2|abbr=on}}におよぶ<ref>{{Cite book|last=Brooke |first=Michael |year=2004 |title=Albatrosses And Petrels Across The World |location=Oxford |publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0-19-850125-0|pages=}}</ref> 。最も高い鳥類の[[生物多様性|多様性]]は熱帯地方で起こっている。以前には、この高い多様性は熱帯でのより高い[[種分化]]の変化率によるものと考えられていたが、近年の研究では、高緯度地方の高い種分化の比率が、熱帯よりも大きい[[絶滅]]率によって、相殺されていることがわかった<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Weir |first=Jason T. |month=March |year=2007 |title=The Latitudinal Gradient in Recent Speciation and Extinction Rates of Birds and Mammals |journal=Science |volume=315 |issue=5818 |pages=1574–76 |doi=10.1126/science.1135590 |pmid=17363673 |issn=0036-8075 |last2=Schluter |first2=D}}</ref>。鳥類のさまざまな科が、世界中の海洋での生活にも適応しており、たとえば、ある種の[[海鳥]]は繁殖のときにだけ上陸し<ref name = "Burger">{{Cite book|last=Schreiber |first=Elizabeth Anne |coauthors=Joanna Burger |year=2001 |title=Biology of Marine Birds |location=Boca Raton |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=0-8493-9882-7|pages=}}</ref>、また、ある[[ペンギン|ペンギン類]]は {{convert|300|m|ft|-2|abbr=on}}以上潜水した記録を持ち<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sato |first=Katsufumi |date=1 May 2002|title=Buoyancy and maximal diving depth in penguins: do they control inhaling air volume? |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |volume=205 |issue=9 |pages=1189–1197 |pmid=11948196 |url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/205/9/1189 |issn=0022-0949 |author2=N |author3=K |author4=N |author5=W |author6=C |author7=B |author8=H |author9=L |accessdate=2014-06-28}}</ref>、ときに{{convert|500|m|ft|-2|abbr=on}}以上潜水して採餌するとされる<ref>{{Cite book|和書 |author=佐藤克文 |year=2011 |title=巨大翼竜は飛べたのか - スケールと行動の動物学 |publisher=[[平凡社]] |series = [[平凡社新書]] |isbn=978-4-582-85568-5 |pages=30-31頁、59頁}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類のなかには、人為的に[[外来種|移入]]された地域で、繁殖個体群を確立した種がいくつもある。これらの移入のなかには計画的になされたものもあり、たとえば[[コウライキジ]]は、[[狩猟]]鳥として世界中に移入された<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hill |first=David |coauthors=Peter Robertson |year=1988 |title=The Pheasant: Ecology, Management, and Conservation |location=Oxford |publisher=BSP Professional |isbn=0-632-02011-3|pages=}}</ref>。そのほか偶発的なものとしては、飼育下から逃げ出し(かご抜け)、北アメリカの複数の都市で野生化した[[オキナインコ]]の安定個体群の確立のような例もある<ref>{{cite web|last=Spreyer |first=Mark F.|coauthors=Enrique H. Bucher|year=1998|title=Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus)|work=The Birds of North America|publisher=Cornell Lab of Ornithology|url=http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/322 |doi=10.2173/bna.322 |accessdate=2014-06-28}}</ref>。また、[[アマサギ]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Arendt |first=Wayne J. |date=1988-01-01 |title=Range Expansion of the Cattle Egret, (''Bubulcus ibis'') in the Greater Caribbean Basin |journal=Colonial Waterbirds |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=252–62 |doi=10.2307/1521007 |issn=07386028 |jstor=1521007}}</ref>、[[カラカラ (鳥)|キバラカラカラ]]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bierregaard |first=R.O. |year=1994 |chapter=Yellow-headed Caracara |editor=Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott and Jordi Sargatal (eds.) |title=[[w:Handbook of the Birds of the World|Handbook of the Birds of the World]]. Volume 2; New World Vultures to Guineafowl |location=Barcelona |publisher=Lynx Edicions |isbn=84-87334-15-6|pages=}}</ref>、[[モモイロインコ]]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Juniper |first=Tony |coauthors=Mike Parr |year=1998 |title=Parrots: A Guide to the Parrots of the World |location=London |publisher=[[w:Helm Identification Guides|Christopher Helm]] |isbn=0-7136-6933-0|pages=}}</ref>などのように、[[農業|耕作]]によって新たに作られた生息に適した地域に、元来の分布域をはるかに超えて{{仮リンク|鳥類の分布拡大|en| Avian range expansion|label=自然分布を拡大}}していった種もある。

| |

| − | | |

| − | == 解剖学と生理学 ==

| |

| − | {{Main|鳥類の体の構造|{{仮リンク|鳥類の視覚|en|Bird vision}}}}

| |

| − | [[ファイル:Birdmorphology.svg|thumb|300px|鳥類の典型的な外見的特徴。1:[[くちばし]]、2:頭頂、3:[[虹彩]]、4:[[瞳孔]]、5:[[上背]] ([[:en:Bird#Anatomy and physiology|Mantle]])、6:[[小雨覆]] ([[:en:Covert feather#Wing coverts|Lesser coverts]])、7:[[肩羽]] ([[:en:Scapular|Scapular]])、8:[[雨覆]] ([[:en:Covert feather#Wing coverts|Coverts]])、9:[[三列風切]] ([[:en:Tertials|Tertials]])、10:[[尾]]、11:[[初列風切]]、12:下腹、13:[[太股|腿]]、14:[[かかと]]、15:[[跗蹠]] ([[:en:Tarsus (skeleton)|Tarsus]])、16:[[趾 (鳥類)|趾]]、17:[[脛]]、18:[[腹]]、19:[[脇腹|脇]]、20:[[胸]]、21:[[喉]]、22:[[肉垂]] ([[:en:Wattle (anatomy)|Wattle]])、23:過眼線<!-- このキャプションに変更を加えるときは、この図にリンクしている他の記事でのキャプションも確認の上、変更してください。 -->]]

| |

| − | ほかの脊椎動物に比較して、鳥類は数多くの特異な適応を示すボディプラン ([[w:Body plan|body plan]]) を持っており、そのほとんどは{{仮リンク|鳥類の飛翔|en|Bird flight|label=飛翔}}を助けるためのものである。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 骨格 ===

| |

| − | 骨格は非常に軽量な骨から構成されている。含気骨には大きな空気の満たされた空洞(含気腔)があり、[[呼吸器]]と結合している<ref>{{Cite book|和書 |editor=松岡廣繁・安部きみ子 |year=2009 |title=鳥の骨探 |publisher=NTS |series =BONE DESIGN SERIES |isbn=978-4-86043-276-8 |pages=18-19}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Ehrlich |first=Paul R. |coauthors=David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye |title=Adaptations for Flight |url=http://www.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Adaptations.html |year=1988 |work=Birds of Stanford |publisher=[[スタンフォード大学|Stanford University]] |accessdate=2014-06-28}} ''The Birder's Handbook'' ([[パウル・エールリヒ|Paul Ehrlich]], David Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye. 1988. Simon and Schuster, New York.) に基づく</ref> 。成鳥の頭骨は癒合しており縫合線 ([[w:Suture (joint)|suture]]) がみられない<ref name=Gill_51>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、51頁</ref>。[[眼窩]]は大きく、骨{{仮リンク|中隔|en|Septum}}で隔てられている。[[脊椎]]には、頸(首)椎、胸椎、腰椎、尾椎の部位があり、頸椎は可動性が非常に高く、きわめて柔軟であるが、関節は[[胸椎]] ([[w:Thoracic vertebrae|thoracic vertebrae]]) 前部で減り、後部の脊椎骨にはない<ref>{{Cite news|title=The Avian Skeleton |url=http://www.paulnoll.com/Oregon/Birds/Avian-Skeleton.html |work=paulnoll.com |accessdate=2014-06-29}}</ref>。脊椎の最後のいくつかは[[骨盤]]と融合して{{仮リンク|複合仙骨|en|Synsacrum}}を形成する<ref name=Gill_28>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、28頁</ref>。飛べない鳥類をのぞいて、肋骨は平坦になっており、[[胸骨]]は飛翔のための筋肉を結合するために、船の[[竜骨 (船)|竜骨]]のような形状をしている。前肢は翼へと修正されている<ref>{{Cite web|title=Skeleton |url=http://fsc.fernbank.edu/Birding/skeleton.htm |work=Fernbank Science Center's Ornithology Web |accessdate=2014-06-29}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 消化、排泄、生殖 ===

| |

| − | 鳥類の[[消化器|消化器系]]は独特である。まず食べたものを一時的に貯蔵するための[[素嚢]](そのう)がある。素嚢の役割は種類によって異なり、食いだめをする種類や素嚢から吐き戻した食物や素嚢から分泌される[[素嚢乳]]を雛鳥に餌として与える種類がいるほかダチョウ類のように素嚢を持たない種類もいる<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_496>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、496頁</ref>。

| |

| − | 素嚢に蓄えられた食物は[[胃]]に送られるが、胃は前胃と筋胃の二つに分かれている。前胃は腺胃とも呼ばれ、内壁に多数の消化腺があり,消化酵素および酸性分泌物を出す。筋胃は[[砂嚢]](さのう)とも呼ばれ、筋肉が発達しているほか、飲み込んだ砂粒が入っており、この筋胃で食物をすりつぶすことで、歯のないことを補っている<ref>{{Cite journal |和書|author=[[和田勝]] |title=食べて消化する |date=2000-11 |publisher=[[文一総合出版]] |journal=Birder |volume=14 |number=11 |pages=8-9}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Gionfriddo |first=James P. |date=1 February 1995|title=Grit Use by House Sparrows: Effects of Diet and Grit Size |journal=Condor |volume=97 |issue=1 |pages=57–67 |doi=10.2307/1368983 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/files/issues/v097n01/p0057-p0067.pdf |format=PDF |issn=00105422 |author2=Best |accessdate=2014-06-29}}</ref>。ほとんどの鳥類は、飛翔を助けるため、すばやく消化することに高度に適応している<ref name = "Attenborough">{{Cite book|last=Attenborough |first=David |authorlink=w:David Attenborough |year=1998 |title=[[w:The Life of Birds|The Life of Birds]] |location=Princeton |publisher=[[Princeton University Press]] |isbn=0-691-01633-X|pages=}}</ref>。渡りを行う鳥のなかには、腸の蛋白質といった、その体のいろいろな部分からの蛋白質を、渡りの間の補助的なエネルギー源として使用するようになっているものがある<ref name = "Battley">{{Cite journal |last=Battley |first=Phil F. |month=January |year=2000 |title=Empirical evidence for differential organ reductions during trans-oceanic bird flight |journal=[[w:Proceedings of the Royal Society|Proceedings of the Royal Society]] B |volume=267 |issue=1439 |pages=191–5 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2000.0986 |pmid=10687826 |issn=0962-8452 |last2=Piersma |first2=T |last3=Dietz |first3=MW |last4=Tang |first4=S |last5=Dekinga |first5=A |last6=Hulsman |first6=K |pmc=1690512}} (Erratum in ''Proceedings of the Royal Society B'' '''267'''(1461):2567.)</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類は[[爬虫類]]と同様に、基本的には尿酸排泄性である。すなわち、その[[腎臓]]は血液中の窒素廃棄物を抽出して、これを[[尿素]]もしくは[[アンモニア]]ではなく、[[尿酸]]として尿管を経由して腸に排出する。鳥類には[[膀胱]]ないし外部尿道孔がなく(ただしダチョウは例外である)、このため尿酸は半固体の廃棄物として、糞と一緒に排泄される<ref>{{cite web|last=Ehrlich |first=Paul R. |coauthors=David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye |title=Drinking |url=http://www.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Drinking.html |year=1988 |work=Birds of Stanford |publisher=Standford University |accessdate=2014-06-29}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Tsahar |first=Ella |title=Can birds be ammonotelic? Nitrogen balance and excretion in two frugivores |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |volume=208 |issue=6 |pages=1025–34 |year=2005 |pmid=15767304 |doi=10.1242/jeb.01495 |month= March|issn=0022-0949 |url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15767304 |last2=Martínez Del Rio |first2=C |last3=Izhaki |first3=I |last4=Arad |first4=Z }}</ref><ref name=coprodeum>{{cite journal | doi= 10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00006-0 | last1= Skadhauge | first1= E | last2= Erlwanger | first2= KH | last3= Ruziwa | first3= SD | last4= Dantzer | first4= V | last5= Elbrønd | first5= VS | last6= Chamunorwa | first6= JP | title= Does the ostrich (''Struthio camelus'') coprodeum have the electrophysiological properties and microstructure of other birds? | journal= Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology | volume= 134 | issue= 4 | pages= 749–755 | year= 2003 | pmid = 12814783 }}</ref>。ただしハチドリのような鳥類は、条件的アンモニア排泄性であり、ほとんどの窒素廃棄物をアンモニアとして排出することができる<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Preest |first=Marion R. |month=April |year=1997 |title=Ammonia excretion by hummingbirds |journal=Nature |volume=386 |issue= 6625|pages=561–62 |doi=10.1038/386561a0 |last2=Beuchat |first2=Carol A.}}</ref>。さらに鳥類は、[[哺乳類]]が[[クレアチニン]]を排泄するのに対して、[[クレアチン]]を排泄する<ref name = "Gill">{{Cite book|last=Gill |first=Frank |authorlink=w:Frank Gill (ornithologist) |year=1995 |title=Ornithology |publisher=WH Freeman and Co |location=New York |isbn=0-7167-2415-4 |pages=}}</ref>。この物質は、ほかの腸の産生物と同じように[[総排出腔]]から出る<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Mora |first=J. |year=1965 |title=The Regulation of Urea-Biosynthesis Enzymes in Vertebrates |journal=[[w:Biochemical Journal|Biochemical Journal]] |volume=96 |pages=28–35 |pmid=14343146 |url=http://www.biochemj.org/bj/096/0028/0960028.pdf |format=PDF |month= July|issn=0264-6021 |last2=Martuscelli |first2=J |last3=Ortiz Pineda |first3=J |last4=Soberon |first4=G |pmc=1206904}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Packard |first=Gary C.|year=1966 |title=The Influence of Ambient Temperature and Aridity on Modes of Reproduction and Excretion of Amniote Vertebrates |journal=[[w:The American Naturalist|The American Naturalist]] |volume=100 |issue=916 |pages=667–82 |doi=10.1086/282459 |jstor=2459303}}</ref>。総排出腔は多目的の開口部で、排泄物はこれを通して排出され、鳥が交尾するときにはそれぞれの[[鳥類の体の構造#生殖器系|総排出腔を接触]]させ、そして雌はそこから卵を産む。これに加えて、多くの種が[[ペリット]](ペレット、pellet)の吐き戻しを行う<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Balgooyen |first=Thomas G. |date=1 October 1971|title=Pellet Regurgitation by Captive Sparrow Hawks (''Falco sparverius'') |journal=[[w:Condor (journal)|Condor]] |volume=73 |issue=3 |pages=382–85 |doi=10.2307/1365774 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/files/issues/v073n03/p0382-p0385.pdf |format=PDF |issn=00105422 |jstor=1365774 |accessdate=2014-06-29}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 呼吸器 ===

| |

| − | 鳥類は、すべての動物群のなかで、最も複雑な[[呼吸器]]を持ったグループのひとつである<ref name = "Gill"/>。鳥が息を吸うとき、新鮮な空気の75%が肺を迂回して、後部 [[気嚢]]に直接流れ込み、これを空気で満たす。後部気嚢とは、肺から広がって骨のなかの気室(含気腔)に繋がっている気嚢のグループである。残りの25%の空気は直接肺に行く。鳥が息を吐くときには、使われた空気が肺から排出され、同時に、後部気嚢に蓄えられていた新鮮な空気が肺に送り込まれる。このようにして、鳥類の肺には息を吸うときにも吐くときにも、常時新鮮な空気が供給されている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Maina |first=John N. |month=November |year=2006 |title=Development, structure, and function of a novel respiratory organ, the lung-air sac system of birds: to go where no other vertebrate has gone |journal=Biological Reviews |volume=81 |issue=4 |pages=545–79 |pmid=17038201 |doi=10.1017/S1464793106007111 |issn=1464-7931}}</ref>。鳥の声は、[[鳴管]]を使って作り出されている。鳴管は筋肉質の鼓室であり、気管の下部末端から分岐し、複数の鼓形膜が組み合わされている<ref>{{Cite journal |和書|author=和田勝 |title=さえずるってどうゆうこと |date=2001-10 |publisher=文一総合出版 |journal=Birder |volume=15 |number=10 |pages=64-65}}</ref><ref name = "Suthers">{{Cite book|last=Suthers |first=Roderick A. |coauthors=Sue Anne Zollinger |chapter=Producing song: the vocal apparatus |editor=H. Philip Zeigler and Peter Marler (eds.) |year=2004 |title=Behavioral Neurobiology of Birdsong |series=Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences '''1016''' |location=New York |publisher=New York Academy of Sciences |isbn=1-57331-473-0 |pages=109–129 |doi=10.1196/annals.1298.041}} PMID 15313772</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 循環器 ===

| |

| − | 鳥類の心臓は、哺乳類と同じく4室(二心房二心室)あり<ref name=Gill_162>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、162頁</ref>、右側の[[大動脈弓]]より[[体循環]]が起こるが、哺乳類では鳥類と異なり左側の大動脈弓による<ref name = "Gill"/><ref>{{Cite journal |和書|author=和田勝 |title=血の巡りをよく |date=2000-12 |publisher=文一総合出版 |journal=Birder |volume=14 |number=12 |pages=8-9}}</ref>。下大静脈は、腎門脈系を経由して、四肢からの血流を受け取る。哺乳類とは異なり、鳥類の[[赤血球]]には[[細胞核|核]]がある<ref>{{Cite journal |和書|author=和田勝 |title=赤い血が流れて |date=2001-01 |publisher=文一総合出版 |journal=Birder |volume=15 |number=1 |pages=66-68}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Scott |first=Robert B. |month=March |year=1966 |title=Comparative hematology: The phylogeny of the erythrocyte |journal=Annals of Hematology |volume=12 |issue=6 |pages=340–51 |doi=10.1007/BF01632827 |pmid=5325853 |issn=0006-5242}}</ref>。[[ニワトリ]]の[[血糖値]]は210-240mg/dlであり、鳥類は[[哺乳類]]に比べて2-3倍の血糖値を示す<ref>芝田 猛、渡辺 誠喜、ウズラの成長に伴う血糖値の変化と血糖成分、日本畜産学会報 Vol. 52 (1981) No.12、P 869-873、http://doi.org/10.2508/chikusan.52.869</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 知覚 ===

| |

| − | [[ファイル:Bird blink-edit.jpg|thumb|left|300px| [[ズグロトサカゲリ]]の目を覆う[[瞬膜]]。]]

| |

| − | [[神経系]]は、鳥類の体の大きさから見ると相対的に大きい<ref name=Gill_208-209>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、208-209頁</ref>。脳において最も発達しているのは、飛翔に関連した機能を司る部位であり、[[小脳]]が運動を調節する一方、[[大脳]]が行動パターンや航法、繁殖行動、営巣などをコントロールする。ほとんどの鳥が貧弱な[[嗅覚]]しか持たないが、顕著な例外として[[キーウィ (鳥)|キーウィ類]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sales |first=James |year=2005 |title=The endangered kiwi: a review |journal=Folia Zoologica |volume=54 |issue=1–2 |pages=1–20 |url=http://www.ivb.cz/folia/54/1-2/01-20.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-01}}</ref>、[[コンドル科|コンドル類]]<ref name="Avian Sense of Smell">{{cite web|last=Ehrlich |first=Paul R. |coauthors=David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye |title=The Avian Sense of Smell |url=http://www.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Avian_Sense.html |year=1988 |work=Birds of Stanford |publisher=Standford University |accessdate=2014-07-01}}</ref>および[[ミズナギドリ目]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lequette |first=Benoit |date=1 August 1989|title=Olfaction in Subantarctic seabirds: Its phylogenetic and ecological significance |journal=The Condor |volume=91 |issue=3 |pages=732–35 |doi=10.2307/1368131 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/files/issues/v091n03/p0732-p0735.pdf |format=PDF |issn=00105422 |author2=Verheyden |author3=Jouventin}}</ref>の鳥などがあげられる。鳥類の[[視覚]]システムは一般に高度に発達している。水鳥は特別に柔軟なレンズを持つことで、空気中の視覚と水中の視覚を両立させている<ref name=Gill_195>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、195頁</ref>。なかには2つの中心窩を持つ種もいる<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wilkie |first=Susan E. |year=1998 |title=The molecular basis for UV vision in birds: spectral characteristics, cDNA sequence and retinal localization of the UV-sensitive visual pigment of the budgerigar (''Melopsittacus undulatus'') |journal=[[w:Biochemical Journal|Biochemical Journal]] |volume=330 |pages=541–47 |pmid=9461554 |month= February|issn=0264-6021 |url=http://www.biochemj.org/bj/330/0541/bj3300541.htm |last2=Vissers |first2=PM |last3=Das |first3=D |last4=Degrip |first4=WJ |last5=Bowmaker |first5=JK |last6=Hunt |first6=DM |pmc=1219171}}</ref>。鳥類は[[4色型色覚]]であり、赤、緑、青の[[錐体細胞]]と同じように、[[紫外線]] (UV) に感度のある錐体細胞を[[網膜]]に持っている。これによりかれらは紫外線を見分けることができ、それは求愛行動にも関係する。多くの鳥類は、紫外線による羽衣(うい)の模様を示すが、これはヒトの目には見えない。すなわち、ヒトの肉眼では雌雄が同じに見えるような鳥でも、その羽毛に紫外線を反射する斑の存在によって見分けられる。雄の[[アオガラ]]の羽毛には、紫外線を反射する冠状の斑があり、求愛行動の際にはポーズを取り、その頸部の羽毛を立てることでディスプレイを行う<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Andersson|first=S.|coauthors=J. Ornborg and M. Andersson |title=Ultraviolet sexual dimorphism and assortative mating in blue tits|journal=Proceeding of the Royal Society B |year=1998 |volume=265 |issue=1395 |pages=445–50 |doi=10.1098/rspb.1998.0315}}</ref>。紫外線はまた、餌を採ることにも使用されている。[[チョウゲンボウ]]の仲間は、[[齧歯類]]が地上に残した紫外線を反射する尿の痕跡を見つけることで獲物を探すことが証明されている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Viitala |first=Jussi |year=1995 |journal=Nature |volume=373 |issue=6513 |pages=425–27 |title=Attraction of kestrels to vole scent marks visible in ultraviolet light |doi=10.1038/373425a0 |last2=Korplmäki |first2=Erkki |last3=Palokangas |first3=Pälvl |last4=Koivula |first4=Minna}}</ref> 。鳥類のまぶたは、瞬きには使用されない。そのかわりに目は、水平方向に移動する3番目のまぶたである[[瞬膜]]によって潤滑されている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Williams |first=David L. |month=March |year=2003 |title=Symblepharon with aberrant protrusion of the nictitating membrane in the snowy owl (''Nyctea scandiaca'') |journal=Veterinary Ophthalmology |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=11–13 |doi=10.1046/j.1463-5224.2003.00250.x |pmid=12641836 |issn=1463-5216 |last2=Flach |first2=E}}</ref>。また、多くの水鳥において、瞬膜は目を覆う[[コンタクトレンズ]]のような働きをする<ref name=Gill_194-195>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、194-195頁</ref>。鳥類の網膜は、櫛状体(櫛状突起、[[w:Pecten oculi|pecten]])と呼ばれる扇状の血液供給システムを持っている<ref name=Gill_197-198>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、197-198頁</ref>。ほとんどの鳥は眼球を動かすことができないが、[[カワウ]]のような例外もある<ref>{{Cite journal |last=White |first=Craig R. |month=July |year=2007 |title=Vision and Foraging in Cormorants: More like Herons than Hawks? |journal=PLoS ONE |volume=2 |issue=7 |pages=e639 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0000639 |pmid=17653266 |last2=Day |first2=N |last3=Butler |first3=PJ |last4=Martin |first4=GR |pmc=1919429 |last5=Bennett |first5=Peter|editor1-last=Bennett|editor1-first=Peter}}</ref>。鳥類のうち、目をその頭部の側面に持つものは広い[[視野]] ([[w:Visual field|visual field]]) を持ち、フクロウのように頭部の前面に両目があるものは、{{仮リンク|双眼視覚|en|Binocular vision}}を持ち、[[被写界深度]]を見積もることができる<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Martin |first=Graham R. |year=1999 |title=Visual fields in Short-toed Eagles, ''Circaetus gallicus'' (Accipitridae), and the function of binocularity in birds |journal=Brain, Behaviour and Evolution |volume=53 |issue=2 |pages=55–66 |doi=10.1159/000006582 |pmid= 9933782 |issn=0006-8977 |last2=Katzir |first2=G}}</ref>。鳥類の[[耳]]には外側の[[耳介]]はなく、耳羽(じう)という羽毛に覆われているが<ref name=Gill_200>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、200頁</ref>、[[フクロウ科|フクロウ類]]の{{仮リンク|トラフズク属|en|Asio}}、{{仮リンク|ワシミミズク属|en|Horned owl}}、{{仮リンク|コノハズク属|en|Scops owl}}ような鳥では、頭部の羽毛が耳のように見える房(羽角、うかく)を形成する。[[内耳]]には[[蝸牛]](かぎゅう)があるが、哺乳類のような螺旋状ではない<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Saito |first=Nozomu |year=1978 |title=Physiology and anatomy of avian ear |journal=The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America |volume=64 |issue=S1 |pages=S3 |doi=10.1121/1.2004193}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 化学的防御 ===

| |

| − | 数種の鳥類は、捕食者に対して化学的防御を用いることができる。一部の[[ミズナギドリ目]]の鳥は、攻撃者に対して不快な油状の胃液 ([[w:Stomach oil|Stomach oil]]) を吐き出すことができ<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Warham |first=John |date=1 May 1977|title=The Incidence, Function and ecological significance of petrel stomach oils |journal=Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society |volume=24 |pages=84–93 |url=http://www.newzealandecology.org/nzje/free_issues/ProNZES24_84.pdf |format=PDF |doi=10.2307/1365556 |issn=00105422 |issue=3 |jstor=1365556 |accessdate=2014-07-04}}</ref>、また、[[ニューギニア島|ニューギニア]]産の数種の[[ピトフーイ|ピトフーイ(ピトフィ)類]](モリモズ類)の数種は、その皮膚や羽毛などに強力な神経毒を持っており<ref name=Yamashina2006_174-177>[[#山階2006|山階鳥研 (2006)]]、174-177頁</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Dumbacher |first=J.P. |month=October |year=1992 |title=Homobatrachotoxin in the genus ''Pitohui'': chemical defense in birds? |journal=Science |volume=258 |issue=5083 |pages=799–801 |doi=10.1126/science.1439786 |pmid=1439786 |issn=0036-8075 |last2=Beehler |first2=BM |last3=Spande |first3=TF |last4=Garraffo |first4=HM |last5=Daly |first5=JW}}</ref>、これは寄生虫に対する防御と考えられている<ref name=Yamashina2006_175>[[#山階2006|山階鳥研 (2006)]]、175頁</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 性 ===

| |

| − | 鳥類には2つの性別、すなわち雄と雌がある。鳥類の性は、哺乳類が持っているXとYの染色体ではなく、[[Z染色体|ZとWの性染色体]]によって決定される。雄の鳥は、2つのZ染色体 (ZZ) を持ち、雌の鳥はW染色体とZ染色体 (WZ) を持っている<ref name=Gill_401-402>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、401-402頁</ref>。鳥類のほとんどすべての種において、個々の性別は受精の際に決定される。しかしながら、最近の研究によって、[[ヤブツカツクリ]]では、孵化中の温度が高いほど、雌に対する雄の[[性比]]が高くなったことから、[[性決定#温度依存性決定|温度依存性決定]] ([[w:Temperature-dependent sex determination|Temperature-dependent sex determination]]) が証明された<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Göth|first=Anne|title=Incubation temperatures and sex ratios in Australian brush-turkey (''Alectura lathami'') mounds|journal=Austral Ecology|year=2007|volume=32|issue=4|pages=278–85|doi=10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01709.x}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 羽毛、羽衣と鱗 ===

| |

| − | {{Main|羽毛|風切羽}}

| |

| − | [[ファイル:African Scops owl.jpg|alt= 目を閉じたフクロウが、同じような色をした木の幹の前にいる。部分的に木の葉に隠れている。|thumb|left|{{仮リンク|アフリカコノハズク|en|African scops owl}}は羽衣によって、周囲の風景に溶け込むことができる。]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | 羽毛は(現在では真の鳥類であるとは考えられていない[[羽毛恐竜|恐竜の一部]]にも存在するが)、鳥類に特有の特徴である。羽毛によって飛翔が可能になり、断熱によって[[体温#体温調節|体温調節]] ([[w:Thermoregulation|thermoregulation]]) を助け、そしてディスプレイやカモフラージュ、情報伝達にも使用される<ref name=Gill_100>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、100頁</ref>。羽毛にはいくつもの種類があり、それぞれが、個々のさまざまな目的に応じて機能している。羽毛は皮膚に付属した上皮成長物であり、羽域(羽区、pterylae)と呼ばれる、皮膚の特定の領域にのみ生ずる<ref name="Shigeta199708">{{Cite journal |和書|author=茂田良光 |title=鳥類の羽毛と換羽 |date=1997-8 |publisher=文一総合出版 |journal=BIRDER |volume=11 |number=8 |pages=27-33}}</ref>。これらの羽域の分布パターン(羽区分布、pterylosis)は分類学や系統学で使用されている。鳥の体における羽毛の配列や外観を総称して、羽衣 ([[w:Plumage|plumage]]) と呼ぶ<ref name="Shigeta199708"/>。羽衣は、同一種のなかでも、年齢、[[社会的地位]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Belthoff |first=James R. |date=1 August 1994|title=Plumage Variation, Plasma Steroids and Social Dominance in Male House Finches |journal=The Condor |volume=96 |issue=3 |pages=614–25 |doi=10.2307/1369464 |issn=00105422 |author2=Dufty, |author3=Gauthreaux,}}</ref>、[[性的二形|性別]]によって変化することがある<ref>{{cite web|last=Guthrie| first=R. Dale|title=How We Use and Show Our Social Organs |work=Body Hot Spots: The Anatomy of Human Social Organs and Behavior |url=http://employees.csbsju.edu/lmealey/hotspots/chapter03.htm |accessdate=2014-07-05 |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20070621225459/http://employees.csbsju.edu/lmealey/hotspots/chapter03.htm |archivedate = June 21, 2007}}</ref> 。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 羽衣は定期的に生え変わっている(換羽、[[w:Moulting|moult]])。鳥の標準的な羽衣は、繁殖期のあとに換羽したものであり、非繁殖羽 (Non-breeding plumage) として知られている。あるいはハンフリー・パークスの用語 ([[w:Humphrey-Parkes terminology|Humphrey-Parkes terminology]]) によれば「基本」羽 ("basic" plumage) である。繁殖羽、あるいは基本羽の変化したものは、ハンフリー・パークスの用語法によれば「交換」羽 ("alternate" plumages) として知られる<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Humphrey |first=Philip S. |date=1 June 1959|title=An approach to the study of molts and plumages |journal=The Auk |volume=76 |pages=1–31 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Auk/v076n01/p0001-p0031.pdf |format=PDF |doi=10.2307/3677029 |issn=09088857 |issue=2 |jstor=3677029 |accessdate=2014-07-05}}</ref>。ほとんどの種で、換羽は年1回起こるが、なかには年2回換羽するものもあり、また、大型の猛禽類は、何年かに1回だけ生え変わるものもある。換羽のパターンは種ごとに異なる。[[スズメ目]]の鳥に見られる一般的なパターンは、初列風切が外側に向かって(遠心性換羽)、次列風切は内側に向かって(求心性換羽)<ref name="Shigeta199708"/>、そして尾羽が中央から外側に向かって生え変わっていく(遠心性換羽)<ref name=Gill_129 /><ref>{{cite web|first=Robert B|last=Payne|title=Birds of the World, Biology 532|url=http://www.ummz.umich.edu/birds/resources/families_otw.html|publisher=Bird Division, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology|accessdate=2007-10-20}}</ref>。スズメ目の鳥では、[[風切羽]]は、最も内側の初列風切から始まり、一度に左右1枚ずつ生え変わる。初列風切の内側半分(6番目の第5羽)が生え変わると、最も外側の三列風切が抜け始める。最も内側の三列風切が換羽したあと、次列風切が最も外側から抜け始め、これがより内側の羽毛へと進行していく。初列雨覆は、それが覆っている初列風切の換羽に合わせて生え変わる<ref name="Shigeta199708"/><ref name="pettingill">{{Cite book|author=Pettingill Jr. OS|year=1970|title=Ornithology in Laboratory and Field|isbn=808716093|publisher=Burgess Publishing Co}}</ref>。[[ハクチョウ|ハクチョウ類]]<ref name=Yamashina2004_64-66>[[#山階2004|山階鳥研 (2004)]]、65頁</ref>、[[雁|ガン類]]、[[カモ|カモ類]]といった種は、すべての風切羽が一度に抜け、一時的に飛ぶことができなくなるほか<ref name="debeeretal">{{cite web|url= http://web.uct.ac.za/depts/stats/adu/pdf/ringers-manual.pdf |format=PDF |year=2001 |author=de Beer SJ, Lockwood GM, Raijmakers JHFS, Raijmakers JMH, Scott WA, Oschadleus HD, Underhill |title=SAFRING Bird Ringing Manual |page=60 |accessdate=2014-07-05}} </ref>[[アビ属|アビ類]]<ref name=Yamashina2004_64-66 />、[[ヘビウ属|ヘビウ類]]、[[フラミンゴ|フラミンゴ類]]、[[ツル|ツル類]]、[[クイナ科|クイナ類]]、 [[ウミスズメ科|ウミスズメ類]]にもこのような種がある<ref name="Shigeta199708"/>。一般的な様式として、尾羽の脱落と生え変わりは、最も内側の一対から始まる<ref name="pettingill"/>。しかし、[[キジ科]]の[[セッケイ|セッケイ類]]においては、外側尾羽の中心から換羽が始まり、双方向への進行が見られる<ref name=Gill_129>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、129頁</ref>。[[キツツキ科|キツツキ類]]や[[キバシリ科|キバシリ類]]の尾羽では、遠心性換羽は少し変更され、これらの換羽は内側から2番目の一対の尾羽から始まり、そして一対の中央尾羽で終わる。これによって木をよじ登るのための尾羽の機能を維持している<ref name="pettingill"/><ref>{{Cite journal |first1=Mayr |last1=Ernst |first2=Mayr |last2=Margaret |year=1954|title=The tail molt of small owls |journal=The Auk |volume=71 |issue=2 |pages=172–178 |url=http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v071n02/p0172-p0178.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-05}}</ref>。営巣に先立って、ほとんどの鳥類の雌は、腹に近い羽毛を失うことで、皮膚の露出した{{仮リンク|抱卵斑|en|Brood patch}}を得る。この部分の皮膚は血管がよく発達し、鳥の抱卵の助けになる<ref name=Gill_450-451>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、450-451頁</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Turner |first=J. Scott |year=1997 |title=On the thermal capacity of a bird's egg warmed by a brood patch |journal=Physiological Zoology |volume=70 |issue=4 |pages=470–80 |doi=10.1086/515854 |pmid=9237308 |month= July|issn=0031-935X}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[ファイル:Red Lory (Eos bornea)-6.jpg|alt= 黄色のくちばしをした赤いインコが翼の羽をくわえている。|upright|right|thumb|ヒインコ (''[[w:Eos bornea|Eos bornea]]'') の羽繕い]]

| |

| − | 羽毛はメンテナンスが必要であり、鳥類は毎日、羽繕いや手入れを行い、かれらは日常の9%前後をこの作業に費やしている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Walther |first=Bruno A. |year=2005 |title=Elaborate ornaments are costly to maintain: evidence for high maintenance handicaps |journal=Behavioural Ecology |volume=16 |issue=1 |pages=89–95 |doi=10.1093/beheco/arh135}}</ref>。くちばしは、羽毛から異物のかけらを払い出すだけではなく、{{仮リンク|尾腺|en|Uropygial gland}}からの[[蝋]]のような分泌物を塗ることにも使われる。この分泌物は羽毛の柔軟性を守り、[[抗菌薬]]としても働き、羽毛を劣化させる[[細菌]]の成長を阻害する<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Shawkey |first=Matthew D. |year=2003 |title=Chemical warfare? Effects of uropygial oil on feather-degrading bacteria |journal=[[w:Journal of Avian Biology|Journal of Avian Biology]] |volume=34 |issue=4 |pages=345–49 |doi=10.1111/j.0908-8857.2003.03193.x |last2=Pillai |first2=Shreekumar R. |last3=Hill |first3=Geoffrey E.}}</ref>。この作用は、アリの分泌する[[ギ酸]]によって補われているとされ、鳥類は羽毛の寄生虫を取り除くために、[[蟻浴]]として知られている行動を通してこれを得ると考えられている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ehrlich |first=Paul R. |year=1986 |title=The Adaptive Significance of Anting |journal=The Auk |volume=103 |issue=4 |page=835 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Auk/v103n04/p0835-p0835.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類においては、羽毛が[[紫外線]]の皮膚への到達を妨げている。鳥類は、皮膚から[[皮脂]]を分泌し、羽毛を[[グルーミング|羽繕い]]することによって口から[[ビタミンD]]を摂取しているとの説もある。この説は毛皮を有する哺乳類にも該当する<ref>{{cite book |first1=Sam D. |last1=Stout |first2=Sabrina C. |last2=Agarwal |last3=Stout |first3=Samuel D. |title=Bone loss and osteoporosis: an anthropological perspective |publisher=Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers |location=New York |year=2003 |isbn=0-306-47767-X}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類の[[鳥類の体の構造#鱗|鱗]](うろこ)は、くちばしや、鉤爪、蹴爪と同じくケラチンから作られている。鱗は主に[[趾 (鳥類)|趾]](あしゆび)や跗蹠(ふしょ)に見られるが、種によっては踵(かかと)のずっと上の部位まで見られるものもある。[[カワセミ科|カワセミ類]]や[[キツツキ科|キツツキ類]]を除いて、大部分の鳥の鱗はほとんど重なっていない。鳥類の鱗は、爬虫類や哺乳類のものと[[相同|相同性]]であると考えられている<ref>{{Cite book|last=Lucas |first=Alfred M. |year=1972 |title=Avian Anatomy—integument |location=East Lansing, Michigan, US |publisher=USDA Avian Anatomy Project, Michigan State University |pages=67, 344, 394–601}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | == 飛翔 ==

| |

| − | {{See also|飛翔|{{仮リンク|鳥類の飛翔|en|Bird flight}}}}

| |

| − | [[ファイル:Restless flycatcher04.jpg|left|alt= 白い胸をした黒い鳥が翼を下に降り下ろして、広がった尾羽を下に向けて飛んでいる。| thumb|羽ばたき飛翔で翼を打ち下ろす{{仮リンク|フタイロヒタキ|en|Restless Flycatcher}}。]]

| |

| − | ほとんどの鳥は{{仮リンク|動物の飛行と滑空|en|Flying and gliding animals|label=飛翔}}することができ、このことが鳥類を、他のほとんどすべての脊椎動物の綱から際立たせている。飛翔はほとんどの種の鳥にとって第一の移動手段であり、繁殖、採餌、そして捕食者からの回避と脱出に用いられる。鳥類は、[[翼型|飛行翼]]として機能するように修正された前肢([[翼]])ばかりではなく<ref name=Gill_131-138>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、131-138頁</ref>、軽量な骨格構造や<ref name=Gill_27・147>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、27頁、147頁</ref>、2つの大きな飛翔のための筋肉(飛翔筋、鳥の全体重の20%以上を占める<ref name=Dic_Ornithology_698>[[#鳥類学辞典|『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)]]、698頁</ref>)である[[大胸筋]]と烏口上筋(うこうじょうきん)といった飛行のためのさまざまな適応が見られる<ref name=Gill_149-151>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、149-151頁</ref>。これに付随して、胸骨に竜骨突起(竜骨稜)が発達すること、脊椎骨や腰骨が癒合すること、尾椎の癒合による尾端骨なども飛翔への適応の一部をなしている<ref name=Gill_28>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、28頁</ref>。短い消化管は体内に蓄積する食物を少なくし、尿酸による排出も排出物の蓄積を減らすことで体の軽量化に貢献する。なお、羽毛や気嚢などは飛行能力の発達に先立って恐竜が持っていたと考えられ、これらは[[前適応]]の例である。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 翼の形状と大きさは、一般的に鳥の飛翔のタイプによって決まる<ref name=Gill_146-147>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、146-147頁</ref>。多くの鳥は、力の必要な羽ばたきによる飛翔と、よりエネルギー要求の低い帆翔(ソアリング、soaring)による飛翔を組み合わせている。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 多くの絶滅種であったような[[飛べない鳥]]は、約60種が現存している<ref>{{Cite book|last=Roots |first=Clive |year=2006 |title=Flightless Birds |location=Westport |publisher=Greenwood Press |isbn=978-0-313-33545-7|pages=}}</ref>。飛行能力の消滅は、隔絶された島嶼の鳥類にしばしば起きるが、おそらくこれは限られた資源と、陸棲の捕食者の不在による<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McNab |first=Brian K. |month=October |year=1994 |title=Energy Conservation and the Evolution of Flightlessness in Birds |journal=The American Naturalist |volume=144 |issue=4 |pages=628–42 |doi=10.1086/285697 |jstor=2462941}}</ref>。[[ペンギン|ペンギン類]]は飛行こそしないが、[[ウミスズメ科|ウミスズメ類]]、[[ミズナギドリ科|ミズナギドリ類]]、[[カワガラス科|カワガラス類]]など、飛翔する鳥類が翼を使って水中を泳ぐ場合と同様の筋肉を使い、水中を「飛行」する<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kovacs |first=Christopher E. |month=May |year=2000 |title=Anatomy and histochemistry of flight muscles in a wing-propelled diving bird, the Atlantic Puffin, ''Fratercula arctica'' |journal=Journal of Morphology |volume=244 |issue=2 |pages=109–25|doi=10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(200005)244:2<109::AID-JMOR2>3.0.CO;2-0 |pmid=10761049 |last2=Meyers |first2=RA }}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | == 生態 ==

| |

| − | 鳥類はほとんどが[[昼行性]]であるが、たとえば[[フクロウ目]]や[[ヨタカ目]]の多くの種は、[[夜行性]]ないし[[薄明薄暮性]](薄明の時間帯に活動する)であり、[[渉禽類]]には潮の干満にあわせて、昼夜に関わりなく採餌する種が多く存在する<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Robert |first=Michel |month=January |year=1989 |title=Conditions and significance of night feeding in shorebirds and other water birds in a tropical lagoon |journal=The Auk |volume=106 |issue=1 |pages=94–101 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Auk/v106n01/p0094-p0101.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 食餌と採餌 ===

| |

| − | [[ファイル:BirdBeaksA.svg|thumb|250px|upright|right|alt= ことなる形状と大きさのくちばしを持つ16種の鳥の頭部の図|くちばしの形状に見られる採餌への適応。]]

| |

| − | 鳥類の食餌は多彩であり、多くの場合、[[蜜]]や[[果実]]、[[植物]]、[[種子]]、[[腐肉|屍肉]]、他の鳥を含むさまざまな小動物などが含まれる<ref name=Gill_32>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、32頁</ref>。鳥には歯がないことから、その[[消化器系]]は、丸のみにした、[[咀嚼]]されていない食物を処理することに適応している<ref name=Gill_26-27・177-178>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、26-27頁、177-178頁</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類には、さまざまな食料において食物ないし餌を得るために、多くの方法を用いる「広食性(多食性)」(ゼネラリスト)と呼ばれるもののほか、特定の食料に時間と労力を集中させるか、単一の方法で食物を得る「狭食性(単食性)」(スペシャリスト)と呼ばれるものがいる<ref name = "Gill"/>。鳥類の採餌方法は種によって異なる。鳥類の多くは、[[昆虫]]や[[無脊椎動物]]、果実、または種子を採る ([[w:Gleaning (birds)|gleaning]])。なかには枝から急襲して昆虫を狩るものもある。[[害虫]]を狙うような種は、有益な「[[生物的防除]]」と見なされ、生物的防除プログラムにおいては、それらの生息が奨励されている<ref name="lwa001">{{cite web|url=http://lwa.gov.au/files/products/land-water-and-wool/pf061365/pf061365.pdf |format=PDF |title=Birds on New England wool properties - A woolgrower guide |publisher=Australian Government - Land and Water Australia |work=Land, Water & Wool Northern Tablelands Property Fact Sheet |author=N Reid |year=2006 |accessdate=2014-07-21}}</ref> 。[[ハチドリ|ハチドリ類]]、[[タイヨウチョウ科|タイヨウチョウ類]]、[[ヒインコ|ヒインコ類]]のような、とりわけ花蜜を採食するものは、特別に適応したブラシ状の[[舌]]を持ち、多くの場合くちばしの形状が[[共進化|共適応]]した花に適するようにデザインされている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Paton |first=D. C. |date=1 April 1989|title=Bills and tongues of nectar-feeding birds: A review of morphology, function, and performance, with intercontinental comparisons |journal=Australian Journal of Ecology |volume=14 |issue=4 |pages=473–506 |doi=10.2307/1942194 |issn=00129615 |first2=. |last2=Baker |jstor=1942194}}</ref> 。[[キーウィ (鳥)|キーウィ]]や[[渉禽類]]は、その長いくちばしを[[探針]]として使い、無脊椎動物を探す。[[シギ科|シギ]]・[[チドリ科|チドリ類]]の間でくちばしの長さと採餌の方法に違いがあることによって、[[ニッチ|生態的地位]](生態的ニッチ)の分離が生じている<ref name=Gill_32-34>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、32-34頁</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Baker |first=Myron Charles |date=1 April 1973|title=Niche Relationships Among Six Species of Shorebirds on Their Wintering and Breeding Ranges |journal=Ecological Monographs |volume=43 |issue=2 |pages=193–212 |doi=10.2307/1942194 |issn=00129615 |first2=. |last2=Baker |jstor=1942194}}</ref>。[[アビ科|アビ類]]、潜水ガモ類 ([[w:Diving duck|Diving duck]])、[[ペンギン|ペンギン類]]、[[ウミスズメ科|ウミスズメ類]]などは、水中で翼ないし足を推進器として使い、その獲物を追いかけるが<ref name = "Burger"/>、それに対して[[カツオドリ科|カツオドリ類]]や[[カワセミ科|カワセミ類]]、[[アジサシ亜科|アジサシ類]]のような飛翔型の捕食者は、獲物に狙いをつけて空中から水に飛び込む。[[フラミンゴ|フラミンゴ類]]、クジラドリ類 ([[w:Prion (bird)|Prion]]) のうちの3種、そして[[カモ|カモ類]]の一部は[[濾過摂食]]を行う<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Cherel |first=Yves |year=2002 |title=Food and feeding ecology of the sympatric thin-billed ''Pachyptila belcheri'' and Antarctic ''P. desolata'' prions at Iles Kerguelen, Southern Indian Ocean |journal=Marine Ecology Progress Series |volume=228 |pages=263–281 |doi=10.3354/meps228263 |last2=Bocher |first2=P |last3=De Broyer |first3=C |last4=Hobson |first4=KA}}</ref><ref>{{ Cite journal |last=Jenkin |first=Penelope M. |year=1957 |title=The Filter-Feeding and Food of Flamingoes (Phoenicopteri) |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences |volume=240 |issue=674 |pages=401–493 |doi=10.1098/rstb.1957.0004 |jstor=92549}}</ref>。[[雁|ガン類]]やカモ類は基本的に[[草食動物]]である。

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[グンカンドリ属|グンカンドリ類]]、[[カモメ科|カモメ類]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Miyazaki |first=Masamine |date=1 July 1996|title=Vegetation cover, kleptoparasitism by diurnal gulls and timing of arrival of nocturnal Rhinoceros Auklets |journal=The Auk |volume=113 |issue=3 |pages=698–702 |doi=10.2307/3677021 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Auk/v113n03/p0698-p0702.pdf |format=PDF |issn=09088857 |last2=Kuroki |last3=Niizuma |last4=Watanuki |first2=M. |first3=Y. |first4=Y. |jstor=3677021 |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>、[[トウゾクカモメ科|トウゾクカモメ類]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bélisle |first=Marc |date=1 August 1995|title=Predation and kleptoparasitism by migrating Parasitic Jaegers |journal=The Condor |volume=97 |issue=3 |pages=771–781 |doi=10.2307/1369185 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/files/issues/v097n03/p0771-p0781.pdf |format=PDF |issn=00105422 |author2=Giroux |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>など一部の種は、[[労働寄生|盗み寄生]](ほかの鳥から食料になるものを奪い取ること)を行う。盗み寄生による食料はいずれの種においても、食料の主要な部分というよりは、むしろ狩猟による収穫を補うものであると考えられている。[[アオツラカツオドリ]]から餌を盗む[[オオグンカンドリ]]についての研究によれば、奪った餌の割合はかれらの食物のうち多くても40%、平均ではわずか5%と見積もられている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Vickery |first=J. A. |date=1 May 1994|title=The Kleptoparasitic Interactions between Great Frigatebirds and Masked Boobies on Henderson Island, South Pacific |journal=The Condor |volume=96 |issue=2 |pages=331–40 |doi=10.2307/1369318 |url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Condor/files/issues/v096n02/p0331-p0340.pdf |format=PDF |issn=00105422 |first2=. |last2=Brooke |jstor=1369318 |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>。他の鳥類には[[腐肉食]]のものがある。なかにはコンドルのように、屍肉に特化したものもあり、また一方ではカモメや[[カラス]]、あるいは他の猛禽類のような日和見的に屍肉を利用するものもある<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hiraldo |first=F.C. |year=1991 |title=Unspecialized exploitation of small carcasses by birds |journal=Bird Studies |volume=38 |issue=3 |pages=200–07 |doi=10.1080/00063659109477089 |last2=Blanco |first2=J. C. |last3=Bustamante |first3=J.}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 水の摂取 ===

| |

| − | 排泄方法と、[[汗腺]]の欠如によって、鳥類の水分に対する生理的要求は軽減されてはいるが、それでも多くの鳥にとって[[水]]は必要である<ref>{{Cite book|year=2005|url=http://irs.ub.rug.nl/ppn/287916626|isbn=90-367-2378-7|last=Engel|first=Sophia Barbara|title=Racing the wind: Water economy and energy expenditure in avian endurance flight|publisher=University of Groningen |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>。ある種の砂漠の鳥は、その食物に含まれる水分だけで、必要とする水をすべて得ることができる。さらにかれらはこれ以外にも、体温の上昇を許容して蒸散冷却(浅速呼吸)による水分の損失を抑えるといった適応を行っていると考えられている<ref>{{Cite journal |first1=B.I. |last1=Tieleman |last2=Williams |first2=J.B |title=The Role of Hyperthermia in the Water Economy of Desert Birds|journal=Physiol. Biochem. Zool. |volume=72 |year=1999 |pages=87–100 |doi=10.1086/316640 |pmid=9882607 |month= January |issue=1 |issn=1522-2152 |url=http://www.biosci.ohio-state.edu/~patches/publication/TielemanWilliams1999_PBZ.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>。[[海鳥]]は[[海水]]を飲むことができ、頭蓋内部に{{仮リンク|塩類腺|en|Salt gland}}を持っている。この塩類腺によって過剰な塩分を、[[鼻孔]]から排出する<ref>{{Cite journal |title=The Salt-Secreting Gland of Marine Birds|last=Schmidt-Nielsen|first=Knut|journal=Circulation|date=1 May 1960|volume=21|pages=955–967|url=http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/21/5/955|issue=5 |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | ほとんどの鳥は水を飲む際に、そのくちばしで水をすくい取り、そして水がのどを流れ落ちるように、頸を上にそらせる。一部の種、ことに乾燥した地域に生息する[[ハト科]]や[[カエデチョウ科]]、[[ネズミドリ科]]、[[ミフウズラ科]]、[[ノガン科]]などに属する種は、水をすする能力があり、その頭を後ろに傾ける必要がない<ref>{{Cite journal |first=Sara L. |last=Hallager |title=Drinking methods in two species of bustards |journal=Wilson Bull. |volume=106 |issue=4 |year=1994 |pages=763–764 |url=https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/wilson/v106n04/p0763-p0764.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-06}}</ref>。砂漠性の鳥の一部は水源に依存し、特に[[サケイ科]]の鳥は、毎日水たまりに集まってくることで有名である。営巣しているサケイ類や、チドリ科の多くの鳥は、その腹の羽毛に水を含ませて、雛に運ぶ<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Water Transport by Sandgrouse |first=Gordon L. |last=MacLean |journal=BioScience |volume=33 |issue=6 |date=1 June 1983 |pages=365–369 |doi=10.2307/1309104 |issn=00063568 |jstor=1309104}}</ref>。なかには、巣の雛に飲ませる水を、自分の[[素嚢]]に入れて運び、あるいは、餌と一緒に吐き戻す鳥もある。ハト科、フラミンゴ目やペンギン目の鳥は、[[素嚢乳]]と呼ばれる栄養分を含んだ液体を分泌して、これを雛に与えるような適応を行っている<ref>{{Cite journal |author=Eraud C |coauthors=Dorie A; Jacquet A & Faivre B |year=2008 |title=The crop milk: a potential new route for carotenoid-mediated parental effects |journal=Journal of Avian Biology |volume=39 |pages=247–251 |doi= 10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04053.x|issue=2}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === 渡り ===

| |

| − | {{Main|渡り鳥}}

| |

| − | たくさんの種の鳥類が、季節ごとの気温の地域差を利用するために渡りをおこない、これによって食料供給や繁殖地の確保の最適化を図っている。これらの渡りの行動は、それぞれのグループによって異なっている。通常、天候条件とともに日長の変化をきっかけとして、多くの陸鳥、[[海鳥]]、[[渉禽類]]および[[水鳥]]が毎年、長距離の渡りに乗り出して行く。これらの鳥類を特徴づけているのは、かれらが繁殖期を[[温帯|温暖な地域]]、ないしは[[北極]]または[[南極]]の極地方で過ごし、そうでない時期を[[熱帯]]地方か、あるいは反対の半球で過ごすことである。渡りに先立って、鳥たちは[[体脂肪]]と栄養の蓄積を大幅に増やし、また一部の体組織の大きさを縮小させる<ref name = "Battley"/><ref name = "Klaassen">{{Cite journal |last=Klaassen |first=Marc |coauthors= |date=1 January 1996 |title=Metabolic constraints on long-distance migration in birds |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |volume=199 |issue=1 |pages=57–64 |pmid=9317335 |url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/reprint/199/1/57 |issn=0022-0949 |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。渡りは、特に食料補給なしに砂漠や大洋を横断する必要がある鳥たちにとって、多くのエネルギーを必要とする。陸棲の小鳥はおよそ{{convert|2500|km|mi|-2|abbr=on}} 前後の飛翔持続距離を持ち、シギ・チドリ類は{{convert|4000|km|mi|-2|abbr=on}}を飛ぶことができるとされ<ref name=Gill_291-293>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、291-293頁</ref>、[[オオソリハシシギ]]は{{convert|11000|km|mi|-2|abbr=on}}の距離を飛び続ける能力がある<ref name=Gill_285>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、285頁</ref><ref name=Higuchi2016_22・112-113>[[#樋口2016|樋口 (2016)]]、22頁、112-113頁</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=The Bar-tailed Godwit undertakes one of the avian world's most extraordinary migratory journeys |url=http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/sowb/casestudy/22 |year=2010 |publisher=[[BirdLife International]] |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。[[海鳥]]も長距離の渡りを行い、なかでも最も長距離の周期的な渡りを行うのが[[ハイイロミズナギドリ]]である。かれらは[[ニュージーランド]]や[[チリ]]で営巣し、北半球の夏を、[[日本]]や[[アラスカ]]、[[カリフォルニア]]沖の北太平洋で、餌を採って過ごす。この季節的な周回移動は、総距離 {{convert|64000|km|mi|-2|abbr=on}} にもおよぶ<ref name=Higuchi2016_113-114>[[#樋口2016|樋口 (2016)]]、113-114頁</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Shaffer |first=Scott A. |year=2006 |title=Migratory shearwaters integrate oceanic resources across the Pacific Ocean in an endless summer |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=103 |issue=34 |pages=12799–12802 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0603715103 |pmid=16908846 |month= August|issn=0027-8424 |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16908846 |last2=Tremblay |first2=Y |last3=Weimerskirch |first3=H |last4=Scott |first4=D |last5=Thompson |first5=DR |last6=Sagar |first6=PM |last7=Moller |first7=H |last8=Taylor |first8=GA |last9=Foley |first9=DG |pmc=1568927 |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。このほかの海鳥では、繁殖期が過ぎると分散して広い範囲を移動するが、一定の渡りのルートを持たない。[[南極海]]で営巣するアホウドリは、繁殖期と繁殖期の間に、しばしば極周回の移動を行っている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Croxall |first=John P. |year=2005 |title=Global Circumnavigations: Tracking year-round ranges of nonbreeding Albatrosses |journal=Science |volume=307 |issue=5707 |pages=249–50 |doi=10.1126/science.1106042 |pmid=15653503 |month= January|issn=0036-8075 |last2=Silk |first2=JR |last3=Phillips |first3=RA |last4=Afanasyev |first4=V |last5=Briggs |first5=DR}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[ファイル:Bar-tailed Godwit migration.jpg|alt=ニュージーランドから韓国に至る、鳥の飛行経路を示す複数の着色した線が描かれている太平洋の地図|thumb|left|人工衛星によって追跡された、[[ニュージーランド]]から北へ向かう[[ハイイロミズナギドリ]]の渡りの経路。かれらは海鳥のなかで最長の{{convert|10200|km|mi|-2|abbr=on}}にもおよぶ、ノンストップの渡りを行う種として知られている。]]

| |

| − | 悪天候を避けたり、食料を得たりするのに必要なだけの、より短い移動を行う鳥もいる。北方の[[アトリ科|アトリ類]]のような大発生する種は、そのようなグループのひとつであり、ある年にはある場所でごく普通に見られたものが、次の年には全くいなくなったりする。この種の渡りは、通常、食料入手の容易さに関連している<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wilson |first=W. Herbert, Jr. |year=1999 |title=Bird feeding and irruptions of northern finches:are migrations short stopped? |journal=North America Bird Bander |volume=24 |issue=4|pages=113–21 |url= https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/nabb/v024n04/p0113-p0121.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。高緯度地方にいた個体が、同種の鳥がすでにいる分布域に移動するように、分布域内でのさらに短距離の渡りをする種もいる。そしてほかのものは、個体群の一部分だけ(普通、雌と劣位の雄たち)が移動する部分的な渡り (partial migration) を行う<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Nilsson |first=Anna L. K. |year=2006 |title=Do partial and regular migrants differ in their responses to weather? |journal=The Auk |volume=123 |issue=2 |pages=537–547 |url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3793/is_200604/ai_n16410121|doi=10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[537:DPARMD]2.0.CO;2 |last2=Alerstam |first2=Thomas |last3=Nilsson |first3=Jan-Åke|issn=0004-8038}}</ref>。部分的な渡りは、地域によって、鳥類の渡り行動の大きなパーセンテージを占めることがある。オーストラリアでの調査によれば、非スズメ目の鳥でその44%が、またスズメ目の鳥でその32%が、部分的な渡りを行っていることがわかっている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Chan |first=Ken |year=2001 |title=Partial migration in Australian landbirds: a review |journal=[[w:Emu (journal)|Emu]] |volume=101 |issue=4 |pages=281–92 |doi=10.1071/MU00034 |url=http://www.publish.csiro.au/paper/MU00034.htm |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。高さの移動 (Altitudinal migration) は、短距離の渡りのひとつの形態で、繁殖期を高地で過ごし、準最適の条件下では、より高度の低い地域に移動するような鳥に見られる。この行動のきっかけは気温の変化であることが最も多く、通常の縄張りが、食料不足によって生息に適さなくなるときに起こるのが普通である<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rabenold |first=Kerry N. |year=1985 |title=Variation in Altitudinal Migration, Winter Segregation, and Site Tenacity in two subspecies of Dark-eyed Juncos in the southern Appalachians |journal=The Auk|volume=102 |issue=4 |pages=805–19 |url=https://84a69b9b8cf67b1fcf87220d0dabdda34414436b-www.googledrive.com/host/0B0PLtJjhTxnkZDAzOGQxY2EtOTIzOS00ZjlkLWJhYmMtYWYzY2QwYmQ2ZjFi/Documents/LEFHE%20Studies%20Real%20Time%20(C.%20Avon)/Ornithological%20Monographs%20and%20Reprints/MAHN-84%20Archives%20Ornithological%20reprints%20(2001-3000)/MAHN-84%20Archives%20Ornithological%20Reprints%202608.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。また一部の種は放浪性である場合もあり、決まった縄張りを持たず、気候や食料の得やすさに応じて移動する。[[インコ]]科の大部分は渡りもしないが定住性でもなく、分散的か、突発的か、放浪性か、あるいは小規模で不規則な渡りをするか、そのいずれかとみなされている<ref>{{Cite book|last=Collar |first=Nigel J. |year=1997|chapter=Family Psittacidae (Parrots)|title=[[w:Handbook of the Birds of the World|Handbook of the Birds of the World]], Volume 4: Sandgrouse to Cuckoos |editor=Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott and Jordi Sargatal (eds.) |location=Barcelona |publisher=Lynx Edicions |isbn=84-87334-22-9|pages=}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類が、膨大な距離を超えて、正確な位置に戻ってくる能力を持っていることは以前から知られていた。1950年代に行われた実験では、[[ボストン]]で放された[[マンクスミズナギドリ]]は、13日後に{{convert|5150|km|mi|-2|abbr=on}} の距離を越えて、[[ウェールズ]]州{{仮リンク|スコーマー島|en|Skomer}}にあったもとの集団繁殖地(コロニー)に帰還した<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Matthews |first=G. V. T. |date=1 September 1953|title=Navigation in the Manx Shearwater |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=370–396 |url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/reprint/30/3/370}}</ref>。鳥は渡りの間、さまざまな方法を使って[[航法|航行]]している。[[昼行性]]の渡り鳥の場合、日中の航行には[[太陽]]が用いられ、夜間は恒星がコンパスとして使用される。太陽を用いる鳥は、日中の太陽の移動を、[[体内時計]]を利用して補正している<ref name=Gill_300>[[#ギル3|ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)]]、300頁</ref>。恒星によるコンパスでは、その方向は、[[北極星]]を取り囲む[[星座]]の位置に依存している<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Mouritsen |first=Henrik |date=15 November 2001|title=Migrating songbirds tested in computer-controlled Emlen funnels use stellar cues for a time-independent compass |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |volume=204 |issue=8 |pages=3855–3865 |pmid=11807103 |url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/204/22/3855 |issn=0022-0949 |author2=L |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。ある種の鳥たちはこれらの航法を、特殊な[[光受容体]]による地球の[[地磁気]]を検知する能力によってバックアップしている<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Deutschlander |first=Mark E. |date=15 April 1999|title=The case for light-dependent magnetic orientation in animals |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |volume=202 |issue=8 |pages=891–908 |pmid= 10085262 |url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/reprint/202/8/891 |issn=0022-0949 |author2=P |author3=B |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | === コミュニケーション ===

| |

| − | {{See also|{{仮リンク|鳥類の鳴き声|en|Bird vocalization}}}}

| |

| − | [[ファイル:Stavenn Eurypiga helias 00.jpg|thumb|alt= 中央部に大きな斑点を持つ翼をそれぞれ左右いっぱいに広げている、大型で褐色の模様の陸鳥| right|[[ジャノメドリ]]の驚くべきディスプレイ。大型の捕食者に擬態している。]]

| |

| − | 鳥類は、基本的に視覚的信号と聴覚信号を使って[[動物のコミュニケーション|コミュニケーション]]を行う。これらの信号は、異種の間(種間)の場合も、同一種内(種内)の場合もある。

| |

| − | | |

| − | 鳥類は、ときには社会的な優位性を判断したり、主張するために羽衣を使用することがあり<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Möller |first=Anders Pape |year=1988 |title=Badge size in the house sparrow ''Passer domesticus''|journal=[[w:Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology|Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology]] |volume=22 |issue=5 |pages=373–78}}</ref>、また、[[性淘汰]]の起こった種のなかでは、繁殖可能な状態にあることを示すために使われることもある。あるいはまた、[[ジャノメドリ]]に見られるように、親鳥が幼い雛を守るため、大型捕食者の[[擬態]]をして[[タカ目|タカ類]]などを脅かし追い払うために羽衣が使われることもある<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Thomas |first1=Betsy Trent |last2=Strahl |first2=Stuart D. |date=1 August 1990 |title=Nesting Behavior of Sunbitterns (''Eurypyga helias'') in Venezuela |journal=The Condor |volume=92 |issue=3 |pages=576–81 |doi=10.2307/1368675 |url= http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/condor/v092n03/p0576-p0581.pdf |format=PDF |issn=00105422 |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>。羽衣のバリエーションはまた、特に異種間において、種の識別を可能にする。鳥類相互の視覚的コミュニケーションには、羽繕いや羽毛の位置の調整(整羽)、突つき、あるいは他のさまざまな行動のような、信号としてではない動作から発展したと考えられる、儀式化されたディスプレイが含まれる。これらのディスプレイは、攻撃ないし服従の信号である場合もあるし、また{{仮リンク|つがい|en|Breeding pair}}(ペア)関係の形成に寄与する場合もある<ref name = "Gill"/>。最も精巧なディスプレイは、求愛の際に行われる。このいわゆる“ダンス”は多くの場合、なし得るいくつもの動作を構成要素とする複雑な組み合わせによって構成されており<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pickering |first=S. P. C. |year=2001 |title=Courtship behaviour of the Wandering Albatross ''Diomedea exulans'' at Bird Island, South Georgia |journal=Marine Ornithology |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=29–37 |url=http://www.marineornithology.org/PDF/29_1/29_1_6.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2014-07-07}}</ref>、雄の繁殖の成功は、そのようなディスプレイの出来栄えに左右されることもある<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pruett-Jones |first=S. G. |date=1 May 1990 |title=Sexual Selection Through Female Choice in Lawes' Parotia, A Lek-Mating Bird of Paradise |journal=[[w:Evolution (journal)|Evolution]] |volume=44 |issue=3 |pages=486–501 |doi=10.2307/2409431 |issn=00143820 |author2=Pruett-Jones}}</ref>。

| |

| − | | |

| − | {{Listen|filename=Troglodytes aedon - House Wren - XC79974.ogg|title=イエミソサザイ|description=[[新北区]]([[北アメリカ]])で一般的な鳴禽である、[[イエミソサザイ]]のさえずり}}

| |

| − | {{Listen|filename=Troglodytes_troglodytes_song.ogg|title=ミソサザイ|description=[[旧北区]]に広く分布する、[[ミソサザイ]]の特徴的なさえずり}}

| |

| − | [[鳴管]]によって発せられる鳥類の{{仮リンク|鳥類の鳴き声|en|Bird vocalization|label=地鳴きやさえずり}}は、鳥類が[[音]]によってコミュニケーションを行う際の主要な手段である。このコミュニケーションは、非常に複雑になる場合がある。なかには鳴管の両側をそれぞれ独立して機能させることができる種もあり、これによって2つの異なるさえずりを同時に発声することを可能にしている<ref name = "Suthers"/>。

| |

| − | | |